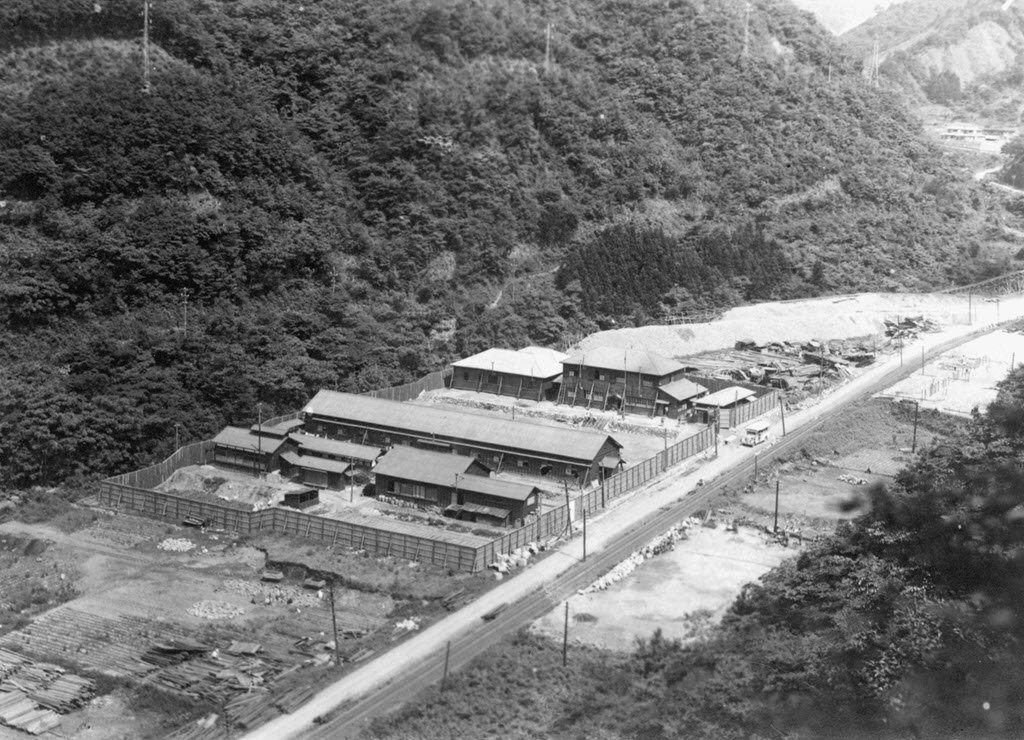

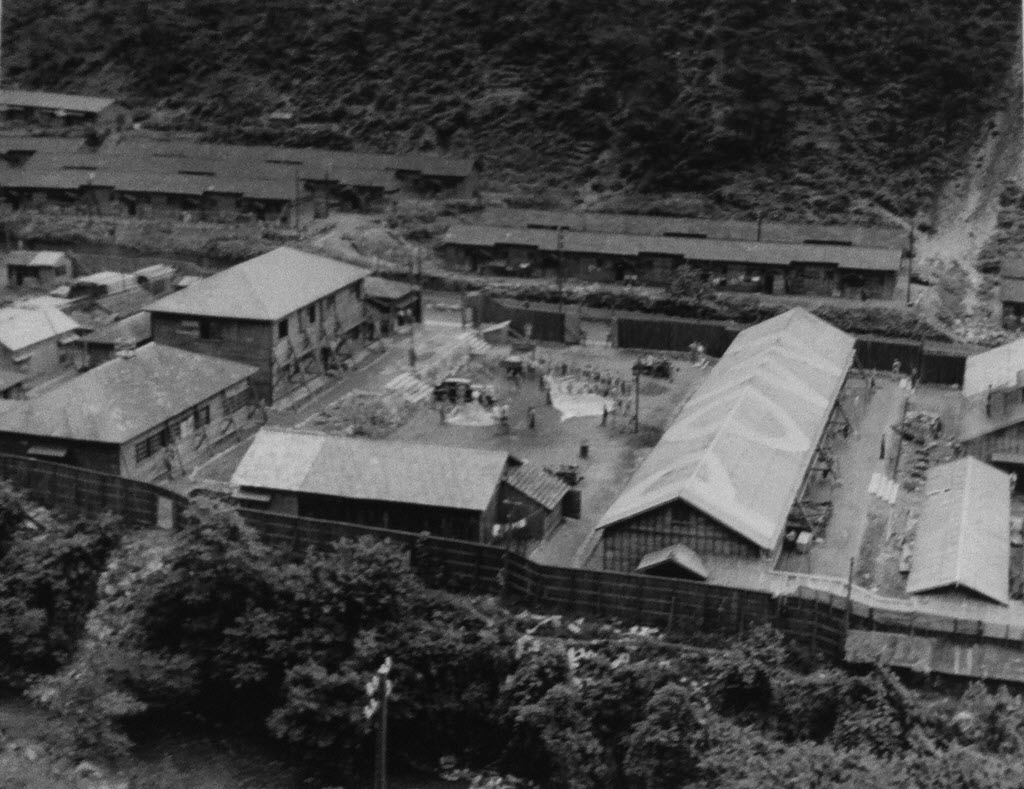

OHASI POW Camp, c 17 August 1945 (Courtesy US Marines)

By George S. MacDonell

AUGUST 15, 2020

The Time: 12 noon on 15 August 1945

The Place: Ohasi Prison Camp in the mountains of Northern Japan

The Situation: Emperor Hirohito of Japan, had just announced to the

people of Japan by Radio that Japan had surrendered unconditionally to

the Allied Powers – the war was over!

To those of us at Ohasi, who had been Prisoners of War for nearly

four years, our first reaction was that we were free.

Now in negotiations with the Japanese Camp Commander we needed to

immediately learn what being “free” isolated in Northern Japan meant.

What did freedom mean to the 150 POWs in the camp including 68

Canadians? We may have won the war, but we were by no means free or out

of danger with the Japanese military still in command.

We immediately began negotiations with our Japanese Camp Commander.

What made these negotiations both dangerous and difficult, were several

factors. The first was the Japanese Military code of “Bushido”, which

demanded a Japanese Officer die fighting or commit Seppuku rather than

accept defeat.

Secondly we knew our Camp Commandant, Lieutenant Zenishi, had written

orders to kill his prisoners “by any means at his disposal” if their

rescue by any Allied forces seemed imminent. And thirdly, we knew that

within a deep deserted mine shaft at the mine and some dynamite, he

could easily dispose of all of us under thousands of tons of rock

without a trace for eternity.

How would this Japanese officer accept defeat and surrender, and

would he obey his Emperor or not? We were soon to find out.

We were in a serious predicament isolated in the mountains of Japan,

with no access to a railway or a travelled highway, with no

transportation of any kind and unable to speak the language.

We knew that the Allied command was not aware of a POW camp in this

remote location and we had no idea of how to acquaint them with our

location or of our existence.

We had no legal standing, we had no money, and we had no agreement

that we could even remain in the camp.

Locked in the mountains we were nowhere near a Japanese residential

area, but there was a very small village located about a mile away.

Because of the devastating American bombing of the past six months,

Japan and its cities were reduced to rubble, its institutions were in

chaos, and millions of Japanese in urban centers were both homeless and

starving.

We had no guarantee of a food supply, our men after years were

already close to starvation, and in the camp we had food supplies, such

as they were, for 3 days.

The victorious American forces were nowhere in sight and still had

not landed in Japan. Despite the fact that our Japanese Camp Commander

was angry, felt dishonoured, and humiliated he appeared to be willing to

negotiate our status.

After some stressful hours we reached an agreement:

1. The Japanese guard and all their weapons would be dismissed from

the camp.

2. The Kempitai, the much feared Military Police of the Japanese Army

would provide temporary Camp security.

3. We could temporarily occupy and live behind the walls of the camp,

and

4. The Camp Commander would stay in the camp in his office with us

for an indefinite period.

With these understandings under way we still had a massive problem.

We had an urgent need to find food for our men and at the same time try

to save those near death.

Despite the risk we decided we must find a way to feed our men. With

trepidation we looted the Japanese stores in the camp for boots,

clothing, soap, leather belts, unbrellas and a host of smaller items. We

then sent out two teams of five men each, under a Sergeant, to see if we

could barter our items for food with the local peasants. We feared this

could provoke a dangerous backlash.

To our delight, the Japanese farmers were not hostile and were happy

to exchange food for our items. But the result of these daily excursions

were not enough to feed the camp.

While this was going on, we realized a secret radio we had been

operating in the camp, might be our key to rescue. By careful monitoring

of our receiving set tuned into Tokyo, we were informed that the

Americans were going to conduct a grid search of the islands of Japan

for prison camps from the air. We followed the broadcast instructions

and immediately painted P.O.W. in eight foot letters in white paint on

the roof of our biggest hut. This appeared to be our only hope – but

could they find us in this isolated area of Japan buried in the

mountains?

Two days later, at about 8 AM, with all of our food gone we heard a

murmur from the sea.

In a few minutes the murmur increased to a distant throb of a single

engined airplane flying at about 3000 feet.

Then suddenly we could see him high above us – a little blue navy

fighter plane with the white stars of the US Navy painted on its wings

and fuselage.

Corsair Aircraft from USS John Hancock, c 17 August 1945

He was east of us and as he proceeded his engine noise began to fade

– he had missed us. Please, God, let him see our camp!

Then all of a sudden the fading engine sound changed its pitch and we

heard the roar of a fighter engine in a dive.

Around the adjacent mountain he came and then down the centre of the

valley where the camp lay with his engine bellowing wide open. At 100

feet, he flew over the centre of the camp.

The camp went wild! Our prayers were answered. Contact at last – now

maybe we had a chance!

He gained altitude to about 7000 feet, and he circled above us – we

assumed he was radioing our location to his base.

Then once again around the mountain he came to fly over the centre of

the camp with his canopy back, his wheels down and flying as slowly as

he dared, he threw out a silver tin box on a long streamer that landed

in the centre of the camp.

In the box were fluorescent strips of cloth and a handwritten note.

The note read “Lieutenant Claude Newton (Junior Grade), USS Carrier John

Hancock. Reported location.”

The written instructions for the cloth strips were simple:

“If you want Medicine, put out M”

“If you want Food, put out F”

“If you want Support, put out S”

We put out “F” and “M”.

Once more he flew over the camp to read our signals on the ground and

waggling his wings, he headed straight out to sea to his floating home –

The Carrier John Hancock.

USS John Hancock, c 17 August 1945

(Courtesy USS Hancock Society)

We were joyous beyond belief and also stunned – now what’s going to

happen? Was that all? What’s next?

Seven hours later at about 3 pm that afternoon, 14 airplanes

approached the camp from the sea. They were blue with white stars on

their wings. While still flown from the Aircraft Carrier Hancock, these

were much larger carrier planes called Torpedo Bombers.

They each made two parachute cargo drops in the center of the camp

and left us with a ton or more of food and medicine. There was a wide

range of items in these supplies from powdered eggs to tins of pork and

beans and there was a large quantity of it.

Some of the medicine was called “Penicillin” with special

instructions for its use since our doctor had never heard of it. This

miracle drug and the food came just in time to save our sick. That night

we had a feast and a mighty party. Despite the doctor’s warnings, the

influx of calories nearly killed us.

Now life had taken a turn for the better. Our men were gaining weight

and the extra food and the new drug was rapidly removing our sick from

the life endangered list.

Also we could see a pathway now to rescue and freedom. Command knew

of our existence.

Time passed until one sunny morning we had another visitor from the

sea. A little blue fighter plane with the familiar white stars on his

wings circled the camp and dropped a note. The note read “Goodbye from

Hancock and good luck. Big Friends Come Tomorrow.”

The plane then flew over the camp once more waggling his wings as he

headed never to return, out to sea to his floating home.

The next day at about 10 a.m., to our amazement, three giant B29

bombers flew in from the sea. Now we knew what “Big Friends” meant, and

they were gigantic.

They circled the camp, flew up-wind a couple of miles and at a very

low altitude began their run. We saw their giant bomb bay doors open and

suddenly a wooden platform – upon which was loaded a number of 60-gallon

oil drums – was dropped. To each oil drum was attached a coloured nylon

chute, and each was packed with tinned rations and supplies of every

kind including new uniforms and footwear. Soon the air was filled with

60-gallon oil drums, swinging leisurely beneath their chutes, coming to

earth over an area of a square mile or so. In one pass they dropped

several tons of food and supplies of all kinds. In the eyes of the

nearby Japanese villagers, we POW’s had gone from starvation and poverty

to wealth beyond measure. It soon occurred to us that, since our new

found wealth was scattered all over hell’s half acre, we should ask the

Japanese civilians in the village to find and bring our oil drums to the

camp. They were happy to do this if we let them keep the nylon chutes for

their women and some of the food as payment. Our bounty was delivered by

our hungry neighbours.

That night, we had another big party, only now everyone was dressed

in a new uniform of his choice: Navy, Army, Marine. The next morning,

promptly at the same time, three lumbering four-engined giants from the

Marianas Islands made their run and again deposited tons of supplies on

Ohasi. Again the industrious Japanese dutifully, with much bowing,

delivered the aerial bounty to their conquerors. By now the camp was

beginning to look like an oil refinery, with unopened 60-gallon oil

drums stacked on the square.

The next day dawned bright and clear, but with a high wind blowing

from the sea. The bombers appeared on time, but this time when they

dropped, some of the parachute lines were snapped in the high winds and

the oil drums fell straight down as deadly missiles. Several hit the

camp, went through the roofs of the huts, hit the concrete floor of the

hut in question and exploded. One such drum was packed with canned

peaches, and I can assure you that when it was over, you could not find

a surface not smeared with peaches anywhere in that hut! There were

several very near-misses of ours and Japanese personnel and several

Japanese houses in the nearby village were damaged. On the next drop,

the same thing happened and as I was fleeing for safety from the camp to

a nearby railroad tunnel, I looked up to see that I was right under a

cloud of falling 60-gallon oil drums now free from their parachutes. It

was a terrifying moment. Was I to be killed after all? Not by a hated

enemy, but by the clumsy kindness of my well-meaning American friends?

Again the camp was hit by drums full of food, clothing and even

toothpaste. Something had to be done. We now had tons of food and

supplies enough for months, and more was arriving.

Was there no limit to their generosity? The aerial supply chain that

had saved us was now a menace. The camp had begun to look as if it had

been shelled by artillery. So we immediately painted two words on the

roof: NO MORE!

The next day, the big friends came from the Marianas and as we

watched with bated breath from the safety of the nearby railroad tunnel,

they circled the camp and, without opening their bomb bay doors, flew

back out to sea, firing off red rockets. It was great fun while it

lasted, but it was getting to be too much of a good thing.

The immediate, organized action to drop so much food, clothing and

medicine into the camp was typical of Americans. When you consider the

cost of the delivery system and the amount of aid they provided and the

speed with which they delivered it, you can only wonder. This generous

and timely response to our needs and to countless other prisoners of the

Japanese, saved many lives and it says a great deal about the values of

our American allies and the mighty civilized nation that stood behind

them. No Canadian, as he gazed in wonder at our American ally’s rescue

efforts, will ever forget their concern for us and their timely

generosity.

Now we settled down to caring for our sick and to some serious

eating. We began to gain a pound a day.

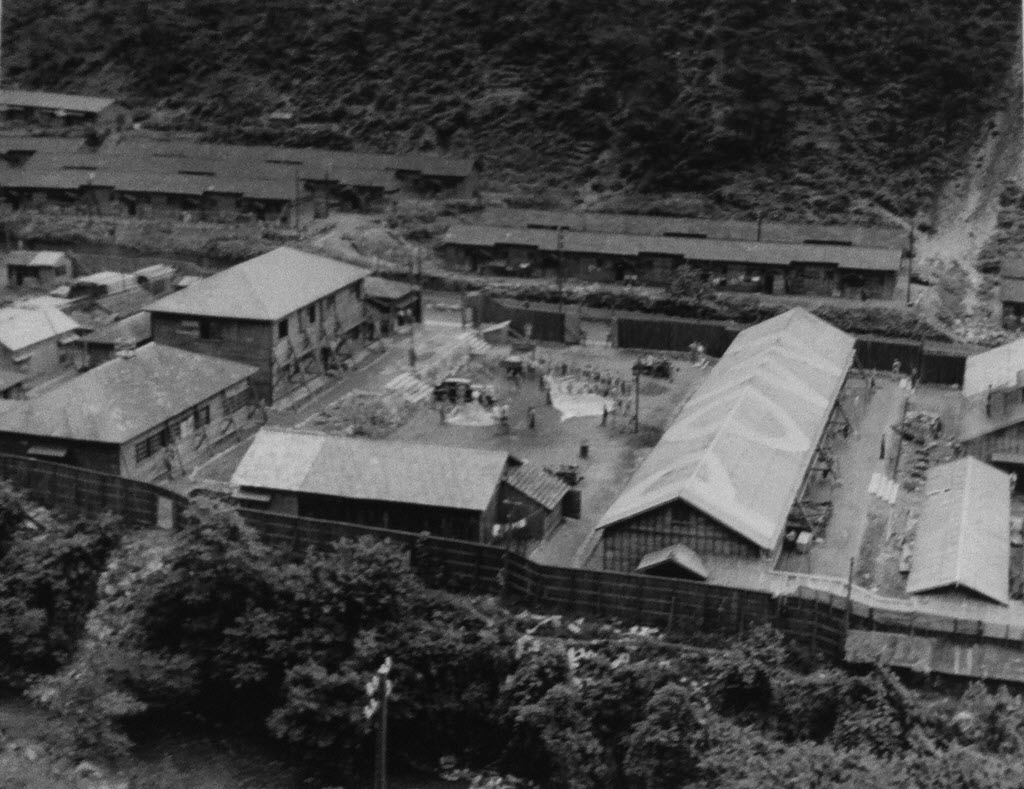

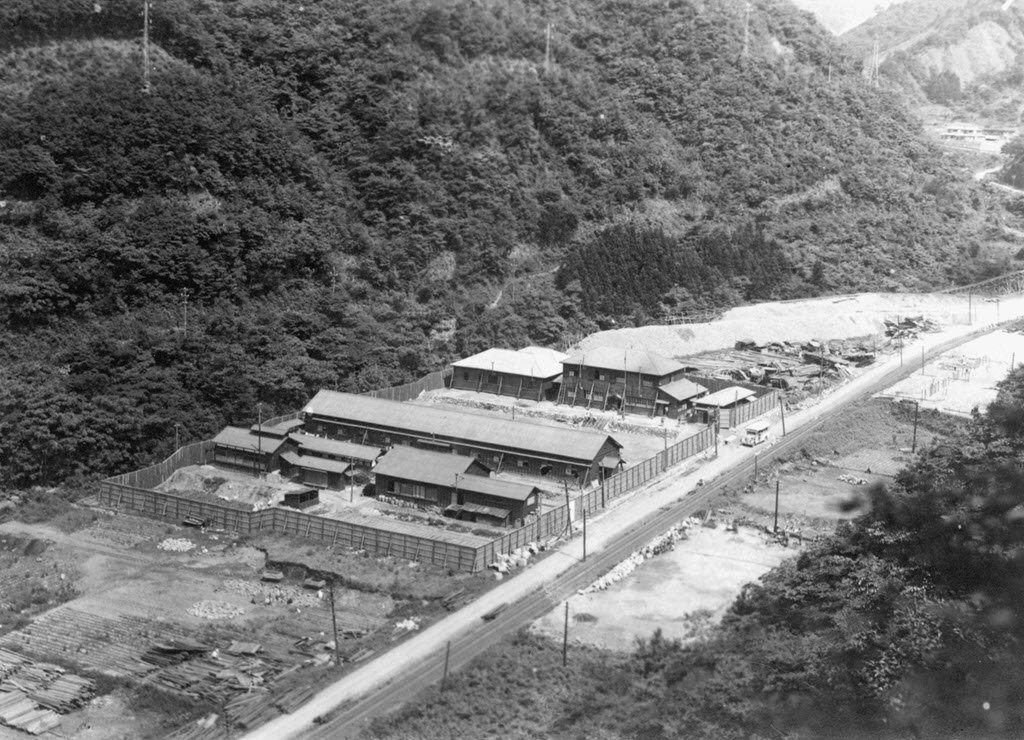

OHASI POW Camp, 15 September 1945 (Courtesy US Marines)

At about this time, I decided to go back to the mine where we had

worked so long. I especially wanted to say goodbye to my fatherly old

foreman of the machine shop who had been kind to me on a personal basis.

It was both a joyous and sad meeting between the old man and the

departing soldier. We were happy that the war was over and we Canadians

could go home and yet we were sad at the knowledge that this would be

our last “Sayonara.” I promised my old Japanese foreman friend that I

would take his earnest advice and return to school as soon as I got

home.

“Hancho, you go Canada now.” These words of explanation whispered to

me on August 15, the day the Emperor spoke, will never be forgotten, nor

will the good will of the old man who spoke them! I developed no hatred

for the people of Japan. Most of them were as kind to us as they could

be under the rules of their brutal military dictatorship. The Japanese

lost 2,900,000 servicemen and civilians during the war. Millions more

were left starving, homeless and wounded.

At every level the war had been a unmitigated disaster for Japan.

The common people of Japan and their loyal soldiers were unwitting

cannon fodder for their cruel and evil rulers who forced them to act out

their crazy dreams of the military conquest of East Asia and, as usual,

it was not just the Chinese, Philippianos and Allied soldiers, but also

the common people of Japan who paid the terrible price for the military

imperialism of their ruling elite.

We also visited the camp graveyard and sadly said one last goodbye to

our comrades who had found their last resting place so far from home. It

seemed to me an unjust reward for such brave young men.

On September 14, a naval airplane flew in from the sea and dropped a

note to inform us that an American naval task force would enter the

nearest harbour to evacuate all prisoners on the following day.

September 15 was a beautiful, clear, warm fall day in Japan. Early in

the morning, an American fleet anchored in a nearby harbour. Large

tank-landing craft beached themselves and in haste disgorged a force of

Marines and their armoured vehicles. Soon, a motorized column of Marines

arrived inland at the Ohasi camp. They were led by a Marine colonel and

they were armed to the teeth. These were veterans of the long Pacific

campaign. They had survived many terrible encounters with the Japanese

in their march across the Pacific and they looked the part. I never saw

a more comforting sight. After our captain saluted the colonel, they

embraced. The colonel then told us how he planned to evacuate us, and

gave specific orders as to how this was to be done. After he issued his

orders, he asked, “Are there any questions?” Our captain said, “Yes, I

have one. Sir. What in the hell took you so long to get here?” That

brought a smile to those tough, weather-beaten faces.

And then we mounted up, said “Sayonara” to Ohasi and after four

years, began the glorious journey home to our loved ones.

From the rear of the last vehicle in the departing column, I saw a

forlorn figure standing in the centre of the empty camp – it was Camp

Commandant Lieutenant Zenichi.

George MacDonell

75TH ANNIVERSARY VICTORY IN JAPAN

AUGUST 15TH 1945-2020

OHASI POW Camp 65 Surviving Soldiers of C-Force, George MacDonell back row, forth from left.

15 September 1945 (Courtesy US Marines) (Click for larger view)

Design & Production

Sue Beard

ORBIT Design Services

647-864-2818

Sue@MissRealEstate.ca

Mike

Babin

Mike

Babin

J

P Bear

J

P Bear

Gerry Tuppert

Gerry Tuppert

Carol Hadley

Carol Hadley

Mark

Purcell

Mark

Purcell

Shelagh Purcell

Shelagh Purcell

Lucette

Mailloux

Lucette

Mailloux

From Robert Cherry

From Robert Cherry Jonathon Reid

Jonathon Reid