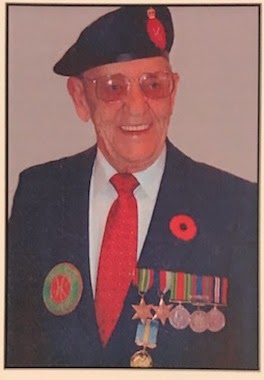

Ralph Maclean profile from April 2019

“It was right over my bed. Picture me with a roof at my feet.

With your friends at your feet. There was a guard on duty and he had

apparently stepped out the door, and the whole shed came down around

him.”

It was New Years’ Eve 1944, and the barracks containing 180 Canadian

Prisoners of War in Japan collapsed under a wet snowfall, with himself

spared by a hole in the roof.

POWs desperately tried to dig out their friends from under the

rubble, but were ordered by Japanese guards to form up and be counted,

lest they attempt an escape in the chaos.

Canadians were left trapped, crying, moaning and entombed.

8 Canadians died that night.

Their frozen bodies were too big for the coffins provided, and their

corpses were broken at the elbows and knees.

Of all things that might kill a Canadian in the Far East during war,

death by snow seemed a cruel irony.

//

Ralph Maclean was from Grindstone Island, Magdalen Islands in the

Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

He recalled his trip to Asia, with his troop ship stopped in Pearl

Harbor in November 1941 to be greeted by ‘Hula’ dancers and a near

mutiny over poor rations of poorly cooked tripe and mutton.

Upon capture on Christmas Day 1941, he was roped together with his

platoon mates with barbed wire, and placed in the middle of the Jockey

Club Stadium.

He had signed up with his best friend Deighton Aitken, who was

separated from him during a diphtheria epidemic.

This disease forms a mucus membrane in your throat suffocating you

and, if this is survived, releases toxins into the bloodstream. Ralph

returned to POW Camp in HK to find Deighton had died.

His platoon Sgt. Bill Pope was from my hometown of Cookshire and my

Grandfather’s best friend from childhood and college.

Bill’s Grandfather was a Senator and his Great-Grandfather was a MP

and the first Minister of Agriculture and Railways.

“He was just perfect. He was a fine man,” recalled Ralph.

Bill died while a POW in Hong Kong.

In Hong Kong, he carried buckets of dirt by hand to move hills to

expand Kai Tak Airport until he was sent to Japan on a ‘draft’ to the

Japanese homeland to work in factories, mines and shipyards.

Locked in the hold of a ‘Hell Ship’, Ralph and other Canadians were

locked in the dark cargo holds far below the waterline, with only

buckets of rice and others to use as bathrooms in two 7 day stretches.

I had not previously published his story last year as I was hoping to

interview him again for a few follow-up questions.

However, Ralph passed away this past March, days before Covid

lockdowns commenced, and before we had a chance to speak again.

May he rest in peace.

Hormidas Fredette from a Remembrance Day

"I used to close my eyes and chomp, chomp, chomp (gestures eating) to

eat the cup of rice so I couldn't see the maggots and bugs in it," he

chuckled about his Prisoner Camp rations.

Meet Hormidas Fredette.

Hormidas is 103 years old.

He is the last remaining Eastern Townships veteran of the Battle of

Hong Kong.

He is from Richmond Quebec, lived in Windsor Quebec and now lives in

New Minas, Nova Scotia.

It is incredible to think he was born in 1917, over a year before the

end of World War 1, and during the Russian Revolution.

"I hope I'll still be around!," he exclaimed when I told him I was

coming to see him.

Pictured, Hormidas is showing me his prized rosary beads, that he

carved from fruit pits and wired together from scrap metal in the

factories he was forced to work in.

Originally from Richmond Quebec, he fought with The Royal Rifles of

Canada in Hong Kong and was a Prisoner of War there and in Japan.

He only met my Grandfather C.Q.M.S. Colin A. Standish, another Royal

Rifle, once: they shared a beer together in Quebec City.

On leave from Valcartier, Hormidas, a Private, spotted my

Grandfather, a NCO, near the Citadelle in Old Quebec.

Hormidas called him over and they drank a beer together in a parking

lot and caught up on Townships life and went their separate ways.

It's funny to think of what people might remember of you someday...

Hormidas fought in the Battle, was pressed into hard labour by the

Japanese and moved hills, bucket by bucket of earth, to construct Kai

Tak Airport in Hong Kong.

In Japan, he had to paint the sides of ships in drydock, where an

earthquake once knocked his scaffolding off the side of the ship leaving

him hanging there until rescued by other workers.

Hormidas returned home, married his sweetheart, and retired to the

Annapolis Valley with his two sons.

I was reluctant to contact Hormidas initially, as there is a moving

video of him (I encourage you to watch it) rejecting the Japanese

apology in 2011 and breaking down on screen.

However, he was a warm and gentle man, who welcomed me into his home

and was eager to share his war experiences without reservation.

I returned the favour from many years ago and brought him a beer.

Jim Trick

Jim Trick Cory Turner, (daughter of Richard Johnson, Winnipeg

Grenadiers)

Cory Turner, (daughter of Richard Johnson, Winnipeg

Grenadiers) J

P Bear

J

P Bear Lori Atkinson Smith

Lori Atkinson Smith

Colin Standish

Colin Standish

Gene Labiuk, Niagara Military Museum

Gene Labiuk, Niagara Military Museum

Gerry Tuppert

Gerry Tuppert Carol Hadley

Carol Hadley

Shelagh Purcell

Shelagh Purcell Lucette

Mailloux

Lucette

Mailloux