Chapter Three - Prisoner in Hong Kong

Captivity is the harshest

teacher.

—Russian Saying

They were learning the reality of

war, these youngsters, getting face to face with the sickening realization

that men get killed uselessly because their generals are stupid, so that

desperate encounters where the last drop of courage has been given, serve

the country not at all, and make the patriot look a fool.

—Bruce Catton, Mr.

Lincoln’s Army

For two or three days after the final shot was fired we were left alone by the Japanese, who no doubt had enough to cope with elsewhere. Potable water was trucked in and there was enough to eat. Most people thought it would be only a matter of a few months before the Americans and British came to our rescue. Nobody mentioned Chiang Kai Shek’s Army any more.

We were told by our leaders that the Japanese officers who had come were very courteous and had complimented the Canadians in particular for their valour. If such was the case it was quite a contrast to the way they had treated the wounded and medical personnel in St. Stephen’s Hospital. The building, just below Stanley, was over-run by the Japanese on Christmas Eve. The Japanese soldiers went on a savage carnage, bayoneting the wounded in their beds, shooting the medical officers and raping the nurses. I was not there, but we all knew about it from the few who had managed to escape and join us in Stanley before the surrender. (The sordid details are in the Appendix.)

On December 30, 1941 we were all lined up in Units. By that time there must have been less than 500 Royal Rifles in the fort. Of the battalion 130 men had been killed and 227 wounded, a 37% casualty rate. Only half of our platoon was present. The entire Stanley Garrison, or at least all who could walk, were marched down the now familiar road, past the areas we fought so hard to retain, to North Point situated across the bay from Kowloon. I was appalled to see how many troops there were. The parade seemed to be about a mile long. Where was everybody when the show was on?

It was a long, sad procession that wound its way back on the narrow, twisting road through Stanley Village, past Palm Villa, Tai Tam and Lye Mun. On the way a few lucky survivors who had been hiding in the hills joined the march. I remember one chap who had been bayoneted by the Japanese after being captured and left for dead. He had crawled into an abandoned pillbox, where he had found some rum which sustained him for over a week. He crawled out to join us and was carried in an improvised stretcher. Nobody expected him to survive, but all took turns helping to carry him, and happily he later made a remarkable recovery.

There was a very obese Warrant officer in the British Army Service Corps... so fat that he could scarcely walk. He fell back further and further in the column, finally bringing up the rear. I think the Japanese purposely let him carry on as he was a caricature of “The Fat Colonial Pig” that they showed in all their propaganda leaflets. As far as I know there was no Japanese brutality on this march like there was in Bataan. He did finally make it to the camp and no doubt looked quite different in a few months.

It was depressing to see the flags of the Rising Sun hanging from every house along the way, but it was only good insurance for the residents.

It was humiliating to see so few guards assigned to guard the straggling column. I suspect this was done purposely to impress the Chinese, in case they needed any further convincing of the superiority of the Imperial Nipponese Army.

In the heat of the afternoon we passed Sau Ki Wan finally reaching North Point. This had been another landing area for the attacking troops and all the remaining buildings and pill-boxes were severely damaged. We were hot, tired and thirsty, even though it was only a twelve mile march. I had only the clothes on my back, a shirt and a pair of British Army shorts that I had scrounged at Stanley, but I had packed several tins of food and biscuits in an army back pack.

We were quite far to the rear of the line when we came to the camp that was to be our new home. I noticed that the guards were relieving everyone of their watches, as they filed through the gate, and quickly slipped mine down my heavy sock. This was one of the few smart things I ever did, as it later became a valuable bargaining item.

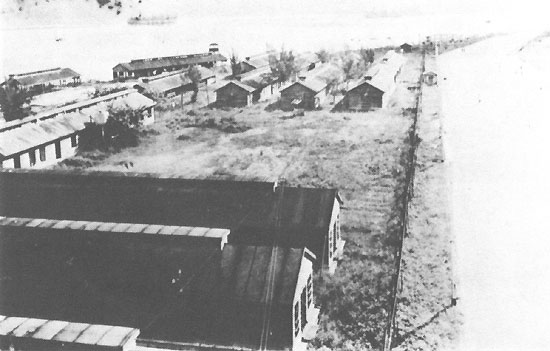

North Point was originally a camp on the outskirts of the city, built to house 300 refugees from China. It was badly damaged during the battle, and several of the huts were burned to the ground. The others had been looted of anything that survived the shelling. To further sweeten the pot, the Japanese had quartered their horses and mules there. It was a mess! A stinking mess! To compound all this, one end of the camp had originally been a dump; the shelling had uncovered all the old garbage, which turned it into a paradise for flies. The other end was littered with dead bodies of Chinese civilians and Japanese pack animals who had been killed by the defenders.

The first month was tough as chaos reigned. There was no water in the camp. It had to be brought in by truck and the delivery of any food was unpredictable. We had nothing to eat for the first two days, and the situation looked grim.

Accommodation was no better, as at first we had all the British and Indian troops as well as the Canadians. We were packed about 200 men into a hut designed to hold perhaps 30 refugees. There was no glass in the windows and in some huts large holes in the roof. Most of us had no blankets and the concrete floor was no Beauty Rest Mattress. Hong Kong can be damp and surprisingly cold at that time of year.

There were no facilities of any kind. In the absence of plumbing we squatted on the sea wall, holding on to a wire fence. I was one of the first to get dysentery and spent some of the worst hours of my life hanging on to that fence. Truly this was the lowest ebb. There were still many bodies floating in the bay. I was holding on to the fence, very weak with fever, nauseated and racked with the cramps that only bacillary dysentery can create, when I glanced down in the water to see a bloated face drift by. I shivered and shook, as the cold damp dawn heightened the chills and fever of the dysentery, and deepened the despair of the breaking day.

I was helped by a Medical Officer of the Indian Army, Dr. Gunn, who gave me some precious M&B sulfa tablets which saved my life. He later died in another camp, but I was able, much later, to make a small payment on my debt to him in a most unexpected way.

When I first came to practise medicine in Vancouver, I saw a young English lady in consultation for a problem that required urgent surgery. She had only recently arrived in this country and was without funds or insurance. She had the same name and by an incredible coincidence was the daughter of the man to whom I owed so much. Luckily, I was able to operate on her and also talk to her mother, which was some small consolation for the widow.

Great credit must be given to those few of our regimental officers and senior N.C.O.s who survived. In North Point the Japanese let the officers run the internal affairs of the camp with very little interference. They organized scrounging parties and these were very effective in recovering a good deal of food and materials from nearby barracks. Also they got permission for other parties to search for the dead and bury them.

In a month most of the British and Indian prisoners were taken over to Kowloon and eventually there were only Canadians and a few Dutch submariners left in North Point Camp.

Within a few weeks latrines were built, plumbing was repaired making water available and cooking facilities were constructed, all from scrounged materials. There was a spirit of cooperation and discipline that was not evident in later camps, particularly in Japan where there was more of a “Dog eat dog” attitude.

For example, I am forever indebted to a real friend, Rifleman JOSS. Hickey, known to all as Manny. For some reason, now forgotten, I was left with no shoes or boots and had developed angry blisters on my feet. Manny, who was not only a talented musician but a skilled artisan as well, made me a pair of sandals. I have no idea where he scrounged the materials or the tools to work with and I still had those sandals when I left Hong Kong for Japan over a year later.

He worked at the hospital where all the dysentery cases were kept. Thank God I had my attack before there was a hospital. Manny gave me a tour of the place which was a small warehouse at the end of the camp. It was dark, dank and smelly; the toilets were old peanut oil cans and anyone who has ever had dysentery, will understand that all too often one could not quite make it to the can. I thought Manny and the other chaps working there deserved medals.

North Point was still badly overcrowded and the diet poor, about 900 to 1000 calories a day, but there were no serious epidemics and only a few deaths. Most of the men were still confident that the Americans and British would relieve us in a few months, an optimistic attitude that I did not share. Morale remained high.

I suppose that few Canadians of our generation have experienced real hunger. Not the hunger of a healthy appetite, or the ravenous feeling after not having food for a few days, but the deep, ever present gnawing sensation in your stomach of having had little food for a long time, and the anxiety of not being certain of any for the next day.

There may be a form of black humour in the fact that the constant topic of conversation was food. It now seems incredible that hour after hour, day after day, men would discuss various recipes and even create new ones. One of the chaps in our platoon talked seriously of introducing riceburgers to Canada. Perhaps he was not so far out of line, as in those days rice was not the common staple it is now in our country, but was only consumed as a pudding.

Food was dispensed from large buckets into an unusual variety of containers. Few still had their original mess tins. Still fewer had cups. Most had tin cans, but there was even the odd china plate. An eagle eye was kept on the server to see that there was no favouritism. I had a tin cup and a spoon that lasted me to the end of the war. In North Point I used an old cookie tin for food, but later in Japan traded up to an American Mess Tin.

A less humorous result of the food deprivation was the pain of “electric feet”, a type of neuritis caused by a deficiency of essential vitamins and proteins. This presented with sharp tingling pains in the legs, but particularly in the feet. The suffering was exacerbated by the presence of any weight, even the thinnest blanket over the feet. Some sought relief by soaking their feet in cold water, if they were lucky enough to find a bucket; but I felt this aggravated the condition, as the water macerated the skin. Oddly enough, although the neuritis soon disappeared with the advent of a healthy diet, it was many years before I could sleep with my feet inside the sheets. No doubt this was psychological, but it was a common experience of many of my fellow P.O.W.s.

Classical beri-beri caused swollen extremities, again particularly the feet and ankles, as well as shortness of breath due to cardiac failure. I think it was more common in Japan than in Hong Kong with our group.

I doubt that anyone escaped one of the more bizarre results of Vitamin B deficiency which we labeled “Strawberry Balls”. This is a manifestation of pellagra, in which the skin of the scrotum becomes red, weeping and desperately itchy. The positions adopted and other methods of seeking relief, I will leave to your imagination.

A less common result of food deficiency was a loss of the sense of balance. I am not sure what the pathology was here; it probably was not any direct action on the inner ear as hearing loss was uncommon, other than the high tone loss and tinnitus (ringing in the ear) from such exposure to the mortar bombs. The balance difficulties were probably due to nutritional damages to the pathways of the spinal cord. These unfortunates sometimes could not walk, even with a cane, while others lurched about often falling.

There were a few cases of blindness and many more of partial loss of vision that sometimes failed to return even with adequate nutrition. Corneal ulcers were more common.

Despite the lack of food, cigarettes were the currency of the camp. They were always in short supply and some men would be so desperate as to sell their meagre food ration, and therefore indirectly sometimes their very life, for a smoke. Some would fight to retrieve a butt discarded by a guard. I knew of two hard drug addicts in the camp; they had no problems in adapting to abstinence. Not so the heavy smokers. It is outrageous that our government has set up a commission to determine if tobacco is addictive. Better one to discover if water is wet.

Sex was not a problem, except possibly for a very privileged few. Perhaps it would be more correct to say lack of sex was never a problem. I find it difficult to understand the high birth rate in some third world countries where the populace are chronically malnourished. If there had been any homosexual desires the absolute lack of any privacy would have discouraged them.

I became close friends with Bill M. He was only a little older than I was, but had already lived a great deal more. He told me he had spent some time in what used to be known as a reform school. In spite of this, he had a most engaging personality, was handsome and bright and remarkably well read. When we were stationed in Valcartier, he stole a case of Scotch whisky from the neighbouring Officers’ Mess of a French-Canadian Regiment. He then, with panache, treated the platoon to an unusual Scotch evening.

He had smuggled a pistol into camp, and in the early days when it was relatively easy to get out had made several forays at night to the great outside, with another friend, “Yank Burns”, who had also smuggled a revolver into the camp. On one of these expeditions they killed a policeman who surprised them as they pilfered a warehouse. I did not take part in these sallies as it was only later that we became buddies.

He loved to tell me of his plans when he got home, how he would rob a particular branch of The Bank of Commerce in Toronto. He spared no detail of his meticulous designs, and I am sure he would have been successful.

I visited that bank after the war when I was in Toronto and felt that Bill had been quite right; it would have been a push-over. Unfortunately, diphtheria deprived Bill of his chance to rob any bank.

He and I did engineer a great operation in North Point, of which I am both proud and ashamed. There was an active black market in the camp, the currency being usually cigarettes and buns. At the end of our hut was the bed of the camp’s chief black marketeer. He had a heavy chest full of his takings that he kept under his bed. (One of the few beds in the hut at that time.)

One night we crept down to his bed, waited to ensure that he was fast asleep and silently slipped it out into the open. We carried it out of the hut, waiting for the sentry to pass, and then made a quick dash to the newly installed showerhouse. Bill quite correctly figured that no one would be there at that time and it would be unlikely for a guard to look in. We emptied the contents into a cotton bag which we brought over to Yank Burn’s hut, again without disturbing anyone and hid it there. Bill insisted that we return the empty box to its original position. I thought that would be really pressing our luck, but it worked. I slipped back into bed and quickly ate three of the buns I had kept.

The next morning the camp was buzzing with exaggerated tales of the escapades. The adjutant threatened dire punishments to the culprits, including turning them over to the Japs. I was very anxious but Bill reassured me as they searched our hut. As he had predicted the authorities went through the hut with a fine comb. We were never discovered and had the good sense to very gradually dispense of our booty, sharing it with Yank and trusted friends. Years later, in Montreal, I met the man we had robbed, and confessed my part in the crime. By then he bore me no malice.

By any standards, Bill had been the most outstanding soldier in our platoon. He always stayed remarkably cool when some of the rest of us tended to panic. He was in his glory when he finally cottoned on to a Tommy gun, which he used most effectively with elegant flair.

I had felt quite strongly that his courage and initiative during the battle should have been recognized with some decoration. The views of a young rifleman were not taken too seriously in the politics of awarding medals.

Another chap in the platoon that I admired a great deal as a soldier was Bernard Castonguay. He was a young, small but tough French-Canadian who, during the battle, looked like a Mexican bandito as he went around with bandoliers of ammunition crossed over his chest. I believe he was given some recognition for his valour.

In camp, I helped him learn to read English and he became an avid reader. He survived the war, but I was saddened to meet him in Montreal and discover that he had become legally blind, no longer able to read. Typically, he was in great spirits and heavily involved with helping other blind people.

After about six months in North Point, the Japanese organized work parties to extend the runways at Kai Tek Airport, which in those days was even more of a menace than it is today. At first these were only small parties and only those who were reasonably fit were chosen to go. Later as the work parties demanded grew larger coincided with a general decrease in health, it became difficult to meet the quota.

I remember well the first time I carried a load of fill in “coolie baskets” at each end of a pole. It requires a good deal of skill to carry heavy loads with the pole angled over the shoulder. In the West a wheel-barrow is preferred. Few of us ever mastered the correct jogging gait to efficiently move a maximum load. This used to upset the guards, one of whom once handed me his rifle to hold while he demonstrated the correct technique. Perhaps we did not try hard enough.

I enjoyed those work parties despite the odd beating for “sabotage”. They were comparatively low key in contrast to the desperate working conditions later encountered in Niigata, Japan.. The straggling walks through the deserted streets of the city were quite a contrast to the pomp and ceremony of our original march down Nathan Road, but it felt great to get outside the fences of the camp. The work was not that bad and we did manage occasionally to foul up things enough to slow any progress.

Most of our section had never mixed sand and cement before and the guards often became exasperated at our dismal performance. Whenever possible we would put in as little cement in the mixture as could escape the attention of the foreman. We later heard that the first planes to use the new runway crashed as they sank into the tarmac. Probably the story was apocryphal but we hoped the story was true.

The work parties also served, unknowingly to most of us, as a contact with the Chinese guerrilla movement who were a source of medications denied to the camp by the Japanese. Plans were also being made for a mass breakout in the event of invasion by the allies. Major Jack Price, the second-in command of The Royal Rifles was a key player in this organization. Unfortunately, the operation was later discovered by the Japanese, with dire consequences.

Sergeant Routledge of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals was one of the key carriers. He would bring messages and materials to Major Price. One day Sergeant Routledge was suddenly arrested by the dreaded Kemptai, the Japanese secret police. He was held in solitary confinement, undergoing interrogation and torture, but did not reveal Major Price’s role. He was sentenced to fifteen years in a Chinese prison in Canton and miraculously survived the war. Certainly Major Price and other involved Canadian officers would have been executed as were three British officers who headed the operation. Sergeant Routledge was decorated for his heroism which saved many lives.

Rumours were the staff of life in prison camp, particularly in the early days of North Point. One of the most curious ones suggested that a trade was in the offing between Canada and Japan, the remaining Canadian prisoners in exchange for the Japanese owned fishing vessels on the West Coast. It seems incredible that anyone with two neurones and a synapse could possibly believe such a patently absurd concoction, but I suspect the majority of the camp at one time were completely taken in by it. No doubt this was a form of therapy. My candid expositions of such hogwash did not endear me to anyone. One learns much too late in life that there is a time to keep your mouth shut.

One aspect of prison life, and I suspect it must be true of any long term unpleasant experience was that it was difficult to imagine ever having lived in freedom. The past seemed unreal, as though it had been a dream. The future appeared increasingly uncertain. I was not one of those who was always sure that he would survive. To me this prospect often appeared most unlikely.

One of my more articulate fellow prisoners has compared our situation to slavery in the ancient world rather than anything in modern warfare. We were the Athenian captives in the quarries of Syracuse, or the surviving males of some sacked city. He pointed out that the feelings of such people were never well documented, as history is written by the winners. The losers expect what they get, and so after a time did we.

In the early days of North Point Camp, there were many Chinese civilians who passed by the fence which fronted on the street. The guards took perverse pleasure, for no apparent reason, in stopping some coolie, tying him up to a pole and bayoneting him, all done with shrieks of laughter from the onlooking guards. I still painfully remember them killing a Chinese woman and her baby when she went down to the seawall beside the camp.

I understand that this was par for the course with the Japanese Army in all their conquered territories. Besides being so brutally perverse it seemed an odd way to win anyone over to “The Greater Co-Prosperity Sphere of East Asia” and the spirit of Bushido. It did leave even the eternal optimists among us with a sinking feeling in their already empty stomachs.

As the months went by and the results of malnutrition became more painfully evident, I realized that we were in for a long stay and the chances of survival were slim. Bill M. had an idea that if we could get up the coast some ninety miles, we had a good chance of meeting some friendly Chinese. According to him junks regularly carried coffins up to that area. He claimed to have the contacts to get us on board and in two of the coffins. Once there, we would be taken care of by the guerrillas.

I was game, as the future looked so grim. In retrospect we would not have had the remotest chance of even getting on first base. If the Japanese didn’t get you, Chinese bandits certainly would. I suspect Bill’s contacts existed only in his fertile imagination.

We went into training, running around the camp ground every night, which was not easy in our weakened condition, and managed to save some food, again very difficult to do on our meagre rations. Fortunately our scheme was aborted. Four Grenadiers escaped a few weeks before our planned date and security was sharply tightened. The hapless Grenadiers were caught and executed without reaching the mainland.

In May, 1942 all of us had been forced to sign pledges that we would not try to escape. Reprisals would be taken on those who remained behind. I think it was because of this pledge and threat that I spent the least unpleasant few months of my time as a P.O.W. A few officers knew that Bill and I had been planning an escape and mistakenly thought that it was all my idea. In August, 1942 when Bowen Road Hospital asked for men to work as orderlies, I was one of the half dozen chosen. I am sure that Smitty, my platoon commander, got this plum for me, not only probably saving my life, but inadvertently having a profound effect on my future career.

Bowen Road Military Hospital was in a delightful setting in the Peak Area. It had been comparatively slightly damaged during the battle and still had many of the conveniences one would expect in a military hospital.

The change from North Point was like going into another world. We slept in beds, even had sheets and mosquito nets. Clean clothes and washing facilities were available. Even the food was better, although not quite enough to prevent the symptoms of malnutrition.

My first week was not exactly perfect, as I again contracted a bad bout of dysentery and had to be hospitalized. I received great care under Dr. Anderson who had been a civilian doctor in Hong Kong. He later came to British Columbia, where I was able to thank him personally. His son was once involved in provincial politics, but is now best known for his fight against pollution from oil tankers.

Although I was low man on the totem pole, I learned a great deal about the care and attention of the sick and dying, as many of the patients were quite literally deathly ill.

Shortly after I arrived in Bowen Road, the Japanese closed North Point Camp, moving all the Canadians to Shamshuipo on the Kowloon side. Unfortunately about this time there was an epidemic of diphtheria. The Japanese would not at first supply any anti-toxin and many of our men died, amongst them Bill M. and Bill Barclay.

Towards the end of the epidemic, the Japanese relented and finally sent some of the terminal cases up to Bowen Road. Through this I had some first hand experience with diphtheria and its inexorable course when untreated.

It is a sad reflection on Quebec Public Health standards of the day that so few of the Royal Rifles had been inoculated against diphtheria. It is even more surprising that the Army did not include it in their routine immunizations. I had never been inoculated and though I nursed many advanced cases I never did contract the disease. In retrospect, I now wonder if two ulcers that persisted on my legs for weeks were not in fact manifestations of the disease. Many of the terminal cases had ulceration of the skin, particularly the scrotum and perineum and less often the nose and face, though these could have been due to malnutrition instead. It was very discouraging to have someone painstakingly recover from the acute bout of disease and then suddenly die from the effects of the diphtheria toxin on the heart a few days later.

Some of the advanced cases of malnutrition were little more than living skeletons. They had reached the stage where they neither desired nor could tolerate food. The doctors felt that the walls of their intestines had become so thin and atrophic that they were incapable of absorbing any nourishment. We would spend hours slowly spooning nourishment into such patients.

Perhaps, most important of all to me personally, was that the experience at Bowen Road was an introduction to Medicine. A harsh introduction, but enough to later save my life in Japan, and still later make me decide to become a doctor. But this is another story.

The Commanding Officer was Colonel Donald C. Bowie. He was a talented surgeon, very mild mannered for one of that specialty, yet able to deal with the Japanese most effectively. He did a fantastic job and was never to receive any recognition for it from the Royal Army Medical Corps, who passed him over for promotion. In a fascinating monograph, “Captive Surgeon in Hong Kong”, he details the history of the hospital during the hostilities and under the Japanese occupation.

I was particularly interested in one paragraph, describing the dysentery ward: “In September 23-24, 1942 in the dysentery division, the patients’ bowels opened 232 times during the night duty hours. Two orderlies were on duty in that division.” I was one of them. The job was hardly a sinecure, but still paradise compared to the camp.

Bowen Road had an adequate library by pre-war standards and I took every advantage of it. Books opened up another world. I had never been an avid reader before, one reason being the lack of good library facilities in Quebec City. The Roman Catholic Church did not allow the Carnegie Foundation to sponsor a library there because books that might be on their Index of prohibited reading would be available. The High School had a very limited supply of books that had to be read in school. Our family certainly could not afford to buy any.

I devoured many of the classics as well as a good share of popular trash. Dickens and Mark Twain were my favourites.

I worked directly under a Corporal Davies of the R.A.M.C. He not only trained me to be an orderly but strongly influenced my whole thinking. He was from Wales and of course was known to all as Dai. We became close friends yet I do not remember ever knowing his real name.

His family had always worked in the coal pits, and he told me tales of the bitter life they endured. He was entirely self-educated, yet was one of the best read and knowledgeable men I have ever met. Naturally he was a communist, and lost no time in trying to indoctrinate me. I can appreciate, almost fifty years later, Winston Churchill’s comment, “Any young man with a heart is a communist, and any old man with a brain is a capitalist.”

Dai also taught me to play bridge. He was a master card player and a born teacher, so we were soon winning some tournaments as well as the odd wagered bun. He was also a wonderful scrounger, an art form that I rapidly acquired and have nurtured even in our wealthy society. We had some great times.

There was almost a surfeit of entertainment talent among the hospital staff, singers, vaudeville artists such as only the English Concert Hall can produce (or tolerate), and several gifted musicians. Besides a piano there were several string and brass instruments. The weekly concerts were a delight. I tried my hand at some poetry, mostly rhymed recitations based on some humorous aspects of prison life. Fortunately for literary posterity almost none of it survived.

Just before Christmas we each received a Red Cross Parcel, a life-saving present for some and a delight for all. Each parcel contained some chocolate, a tin of meat, sugar, a tin of butter, jam, cheese and instant coffee. The odd man ate the whole parcel in one or two orgies, but most of us managed to spread it out over a fortnight. No one has more respect for The Red Cross than any ex P.O.W. Unfortunately the Japanese stole many of the parcels as well as some of the bulk food that had been sent.

Shortly after Christmas I developed a painful, swollen jaw due to an impacted wisdom tooth. I was sick, feverish and thought I had a recurrence of malaria. There was a young dentist on the staff, Captain Fraser. With the limited available tools and local anaesthetics he removed the offending tooth and I am forever grateful for his skilful attention. I remember him very fondly also as one of the few people I could consistently beat at chess.

About this time the Americans began bombing Hong Kong Harbour and the ships in the bay. We would cheer as the planes zoomed by, the first time we had ever seen any from our side. This upset the Japanese who threatened to shoot any such supporters. We still cheered. ... silently. One of Dai’s friends had a clandestine radio and we were disappointed to hear the exaggerated claims of the raid by the B.B.C. There was some consolation, in that they were not nearly as overblown as the ones of the Japanese, when they first raided Kai Tek and destroyed the five old aircraft there. Never believe any “news” in a war.

I had to leave this happy life in about July of 1943, and I was sad to go. Except for Dr. Anderson, I never again heard from my friends there, the staff and doctors to whom I owed so much. I have wondered what happened to Dai Davies. Is he a staunch supporter of Mrs.Thatcher now?

Shamshuipo Camp was much better than North Point in terms of space and facilities. When I arrived the diet had improved considerably as some bulk Red Cross food had been released. It was much more palatable than Bowen Road and more nutritious as well.

Like all camps there was still the problem of keeping clean. Almost everyone was lousy. Spare time was spent locating the lice in the seams of your clothing, and then triumphantly crushing them between your thumbnails. It was good mental as well as physical hygiene.

Bedbugs were another matter. They could make sleep impossible and I can still recall the nauseating stench they left on being squished.

The camp interpreter, Kanoi Inouye, was known as “The Kamloops Kid” as he had been born and raised in Kamloops. Like many Canadian Nisei he had been sent to school in Japan by his parents whose primary allegiance was not in doubt. He was bigger than his colleagues, quite handsome, bright and terribly mean. He made it known that he had been called a yellow bastard in Canada, and that now he was top dog. He was harder on the prisoners than most of the guards, being responsible for many cruel beatings and deaths. So much for being a Canadian. He was condemned to death by the War Crimes Judiciary and was hanged in Hong Kong.

The Commandant, Colonel Suzuki, was commonly known as “The Pig”. Not only was he fat but his features were porcine. He cut a ridiculous figure as he waddled around in his high leather boots, sword almost dragging on the ground, sweat pouring down his neck on to the collar of the white open-necked shirt draped over his tunic.

He had lived in Hong Kong before the war, and like many Japanese residents appeared in uniform after the surrender. During his tenure as commandant he lived high off the hog, being heavily involved in the black market, no doubt selling some of the provisions destined for us, including Red Cross supplies.

Japanese Intelligence had been well served by such people, and I suspect they knew more than our own high command, which isn’t saying very much. It is strange that with all the resources available to the British that their Intelligence network could have been so ill informed.

Apparently there were many Japanese residents who were spies in the pay of Colonel Suzuki at the Japanese Consulate. He also enlisted Wanchai brothel girls and others in close touch with the military. There is the classic story of the barber at the Peninsula Hotel, who appeared after the surrender as Commandant of Stanley Internment Camp, wearing the uniform of a Lieutenant Commander in The Japanese Navy. Japanese business men had laid concrete bases in warehouses in Kowloon that were immediately available for the heavy artillery to use in the devastating barrages against the island.

The Pig used to love to attend the concerts staged in the camp. I only saw one of them, but the production was simply fabulous. Where all the costume material and staging came from is simply incredible. Much of this was due to the vitality and imagination of Jan Solecki. He was a Pole, born and raised in Harbin, who came to Hong Kong not too long before the war started and was a private in the Hong Kong Volunteers. After the war he attended The London School of Economics, and eventually ended up on the staff of The University of B.C., where I got to know him, not as an academic, but a friend.

These concerts did much for the morale of everyone as for an hour or two one was wafted over the barbed wire into another world.

I was only in Shamshuipo for a few weeks and remember little else of my time there. Most of my surviving buddies in the platoon had left on a draft to Japan.. Marvelous rumours told of how they had boarded a great white ship, each had been given a Red Cross parcel and now they were being treated so handsomely in The Land of The Rising Sun. Another draft of 500 were due to leave, and although I did not believe a word of the rumours, I was glad to be included. Not that I had any choice in the matter.

I do not recall this but one of my friends, Bob Manchester, with a better memory than I has described how we were chosen for the draft:

“You may remember that one bright day, we were lined up on one side of the main road that ran through the camp. All those who could make it to the other side of the road won the chance of making this summertime vacation trip.., an all expense one way voyage. Great excitement! Everyone wanted to go but only 500 were called.”

We were divided into two groups, mostly British and Hong Kong Volunteers in one, Canadians and Dutch in the other.

All of us were in good heart as we marched down Nathan Road for the last time. The Royal Rifles were all together, and we whistled our regimental tune “65” to the amusement of the guards. Such optimism was unwarranted as one in three in our group would never leave Japan.

It was late in the summer of 1943. We had been allowed to take whatever clothing we had and whatever else could be scrounged. Some still had Canadian battledress which would be useful in the anticipated colder climate. I only had cotton pants but did have some flannelette pajamas liberated from Bowen Road Hospital, which I thought would make good underwear.

We arrived at the dock, some expecting to see a large white passenger ship; this was not to be. Instead we boarded a small, dirty collier the “Manryu Maru”.

There were two holds in a poor excuse for a ship. Our group, mostly Royal Rifles, was in the forehold of the collier which still had some coal piled in the bow. We could not all lie down at the same time as there was insufficient room to stretch out. There were no toilets, only buckets passed up to the deck when full. It was not The Queen Mary, and I recalled how we had bitched so vehemently at the accommodations on the troopship “Awatea”.

Food and fresh water were lowered in big tubs. Since many were seasick, and unable to eat, the rest of us were better fed than we had been for a long time. The lighting was very dim and there was no room to stretch out, but still some managed to play cards. Others just sat and stared at the steel bulk heads, but most were in surprisingly good spirits.., telling stories of the wonderful breakfasts they used to have when they worked in logging camps, the halcyon days of prohibition in the U.S.A., when a hundred dollars could be made by dragging a sled of liquor across the border at night... and recalling the generosities of the girls in Newfoundland.

After the second day the guards relented and opened the hatches during the day. For those who could control the calls of nature, there was a toilet situated on the aft deck of the ship. To use this you had to ask permission to go “Benjo”, then you were allowed briefly on deck and had to move both yourself and your bowels quickly. One had to literally run a gauntlet of the guards, who were not averse to using the butt of their rifles to hasten your movement. No pun intended. However at night the hatches were closed, so by morning the air was putrid. Since there were no washing facilities, each day, indeed each hour compounded the problem.

It was a relief to get to the port of Taipei. There we were allowed up on deck and enjoyed the luxury of a salt water hosing. White-coated lab technicians came aboard and we were subjected to having a glass tube inserted into the rectum, presumably a test for amoebic dysentery. It must have had the traditional sink test, as no one ever heard of any results, and I am sure that at least twenty-five percent of us were positive. The Japanese had a morbid fear of infections and this type of charade seemed to satisfy them.

From Taipei we sailed through the Inland Sea to Osaka, relieved to arrive. The contingent drafted before us had sailed on the “Lisbon Maru”. It was sunk by an American submarine with great loss of life, the guards shooting those desperately trying to escape from the holds of the sinking vessel. This was not a comforting thought as we lay in the holds, looking at the steel plates of the hull.

We did have one submarine scare shortly after leaving Taipei. All the hatches were battened down and we were warned to be very quiet by the guards. It was a tense time as we were indeed like rats in a trap. Some planes flew over and the emergency ended.

There was a slight drizzle as we walked down the gangplank in Osaka, clutching our meagre possessions, a motley crowd if there ever was one. No two had the same dress, but what I still remember most vividly was the incredible variety of hats.

Our reception committee wore long, white medical gowns and surgical masks. They carried Flit-guns and gave each of us a thorough spraying from head to foot, presumably so we would not contaminate their sacred land. It was probably some phenol solution as those not quick enough to close their eyes suffered for several days.

We were lined up and numbered off several times before being addressed by a rather fat young Lieutenant. He may have been a Nisei as his English was fluent and colloquial. (Many Canadian and American Nisei served in the Japanese Army). He really laid it on, shouting that we must obey every order on pain of death; we would work to help Nippon defeat the crumbling Americans. The war would last a hundred years with divine Nippon victorious. Soldiers who surrendered deserved nothing but contempt. Hardly a Chamber of Commerce welcome, but not all that depressing because we had heard it all before.

Then we marched, or I guess more correctly were herded through narrow streets to the railway station. Bystanders gawked at us and the odd old woman spat on us, but most showed no evident antagonism. No one waved Union Jacks.