Chapter Five - Fears, Hopes and Freedom

I never

saw a man who looked

with such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

which prisoners called the sky.

—Oscar Wilde, The

Ballad of Reading Gaol

Some time after the debacle of the collapse of the hut early in the morning of New Year’s Day, 1944, four of the chaps with pelvic injuries were moved to a small cottage hospital in the city. I was lucky enough to go along with them to care for their needs. This was a welcome change for the five of us and especially interesting for me.

All the Japanese staff were very curious about us and I suspect some of them had never seen any of the terrible enemy before. Most of them were surprisingly civil and when no one was watching some of them touchingly kind. Some of the girls brought us little gifts of food. Since then I have always suspected the Japanese woman to be a different race than the man. Don’t ask me to explain.

We were in a small room about six tatamis wide, each of the injured lads occupied one tatami, so it was not all that easy to look after them. All were in full body casts; it was difficult to keep them clean, fed and entertained. Nevertheless, they were much better off here than they would have been at camp and they all made a good recovery.

At night when all the staff left, I even had the luxury of a hot bath, the first private bath in three years, as I discovered to my surprise we were alone in the building. I cautiously explored in the semi-darkness as I dared not turn on the light. There was a small kitchen and I managed to steal some sugar and cold rice.., taking only enough every night to not arouse suspicions. One time I managed to get two little purple bean cakes, which we all shared.... a delicious triumph!

It all added a little excitement to our stay. Later I wondered if the staff might have known all the time of my pilfering, because the lady who looked after the kitchen always gave me a big smile in the morning.

It all ended too soon. We went back to camp and told great stories how we had been entertained by Geishas, served gourmet meals and at night had difficulty fending off the young girls who had heard stories of the amatory prowess of the Gaijin. I think a few might have believed us.

During our absence, the camp had been relocated. The Shintetsu Iron Foundry Group were moved to a building near the foundry, and we had no contact with them until the end of the war. The Rinko Coal and Marutsu Dock workers were relocated to another building, this time closer to the docks. It was a great improvement over the last camp, which was to be brought up to standards. Even the hard boiled Tokyo staff, brought up to investigate the collapse of the hut had been horrified at the conditions.

Our temporary camp was still very crowded; no adequate washing facilities and too few toilets; no exercise area at all; but the best camp yet. The “hospital”, the quotation marks being obligatory, had windows that could be closed against the snow and had a small stove in the middle of the room, which held about thirty tatamis. About this time we received Red Cross parcels. I suspect Lieutenant Yoshida had kept them hidden, hoping to sell them on the black market, but the Tokyo visitors may have given him a bit of a scare. Even the army was scared of the Kemptai (secret police).

There was also a small shipment of medicines from the Red Cross, including some sulpha drugs for pneumonia, emetine and carbasone for the amoebic dysentery and vitamin pills. I had hoped for dramatic results with the magic medicines, but was disappointed. Those with Beri-Beri still kept their swollen legs when given vitamins; dysentery did not disappear with medications; although those with pneumonia did better, some still died. The real problem was the almost total lack of protein in the diet. Medicine alone could not overcome the loss of resistance due to longstanding malnutrition.

I never was able to accept the inevitable with equanimity. To be admitted to hospital was almost a passport to eternity, as you had to be reduced to a near dehydrated skeleton or have a raging fever and difficult breathing to make the grade. Shorty Pope, our platoon Sergeant, and Bill Knapp, who had been a schoolmate and friend in Quebec City, both died in my arms. There was so much to do and so little that could be done.

What I especially hated to do was prepare the bodies for the wooden box waiting in the hall. On each side, directly beside the body, was a patient lying on a tatami, (we had no beds) perhaps in no better shape than the man had been who had just died. I had to stuff the mouth and rectum with paper, (we had no cotton-wool to spare) before carrying the body out to the waiting box. Most seemed to die at night, so all this could be done in the dark, which was a little less traumatic for everybody. At times, one or two of the orderlies would pull the body on a cart to the crematorium. There was no effort or pretence at any religious ceremony. Nobody cried.

I cannot recall any cases of depression (in the medical sense), nor were there any attempted suicides in our camp. Much later, on investigating this, I was surprised to discover that people under such severe crises are not prone to these problems. It has been shown that there was a marked decline in mental problems during the blitz. We did have one young Mormon lad who developed hallucinations that the Americans were on their way to relieve us, and tried to escape. The tragic results are recorded in the last section of the Appendix. The rest of us were not mad, just sad.

The daily sick parade remained a nightmare. It was held in the evening and few, if any of the men who attended, were fit for work. The camp doctor, Bill Stewart, was in an impossible situation. If he excused too many, the medical corporal, Takeo Takahashi, would abrogate his authority to excuse any. In the chaos, more would suffer and fewer saved. He managed this balancing act very well. Most of the camp understood that it was not easy to give a haggard, coal-blackened derelict of a man a few bismuth powders for his diarrhoea and tell him to try to make the work-parade in the morning. There were remarkably few who abused the system and sometimes disparaged our efforts.

At times Corporal Takahashi would announce that we were using too much medicine and would ceremoniously lock the room opposite his office where all the medications were kept. This did not create too big a problem as I knew where he kept the key, and was able to get what was absolutely necessary at very little risk. I suspected he was selling some medicines in the flourishing black market in town. This was probably the case, as Yoshida, the Camp Commandant, was later proved to have sold food and Red Cross supplies. This was about the time that I had developed a contact through a guard, so it is quite possible we were buying our own medicine back! More on this later.

I have purposefully left the description of atrocities to the appendix, with this one exception, because it still both haunts and inspires me.

James Mortimer was a rifleman who had joined the battalion just before we sailed for Hong Kong. I really did not know him well before prison camp. There he presented as what today we would call a hippie type of person. He had an almost cherubic face, was a gentle soul, always on the scrounge and often on sick parade. I think that were he here today, he would be involved in anti-nuclear war nonviolent demonstrations, environmental protests and the like.

One day early in January, he stole the lunch off the bicycle of a Japanese workman, who had come to do some work in the Commandant’s office. Something any of us would have done if the coast looked clear. Unfortunately, he was caught.

Sergeant Ito, the right hand man of the Commandant, flew into a rage, knocked him about with the flat of his sword, and had him tied up just outside the gate. It was subzero weather with blowing snow. Mortimer had on only cotton pants and worn footwear with no socks. Despite the pleas of Major Fellows and Doctor Stewart he was left outside for over a day.

Finally the guards cut him loose and we carried him into the hospital. After a few hours of warming he recovered consciousness. Miraculously, the upper part of his body was only superficially frozen, and he could move his arms. However his lower limbs were past repair and soon became gangrenous. The smell in the small room of the hospital was overpowering. Ito would not consider sending him to the P.O.W. hospital in Tokyo, perhaps because he would have been reprimanded for such literal overkill for a minor offence.

Mortimer showed incredible courage and tenacity, knowing he had almost no chance of survival. He never complained, joked about his black feet and actually comforted those beside him. He fought the inevitable for almost two months and died in his sleep. I cannot forget this change of character into a person of such strength, a model for us all.

The summer of 1944 brought renewed hope. The weather was a pleasant change and the lice were exchanged for fleas, which were to be preferred. Our morale rose with the news of allied successes in Europe, and Japanese reverses for a change.

Surprisingly, we were remarkably well informed about the news. Our medical room was right next to the guards’ quarters and I was able to pick up the odd newspaper they left lying about. At this time there was no one amongst the prisoners who could read Kanji, (Japanese characters), but the maps of military actions were easy to interpret as they were titled in Katakana, the phonetic script. Bill Stewart had a small Japanese-English dictionary and I became quite proficient in deciphering Katakana, as well as understanding Japanese medical jargon. All this was not without some risk, as the authorities were paranoid beyond belief.

The P.O.W. officers had received pay but had never been given any opportunity to buy anything. Now Yoshida left, and the new commandant permitted them to buy some musical instruments. It was through this that I became friends with George Francis. He was an American Marine Sergeant, but prior to joining the Marines had been a trumpet player in Los Angeles, and had shipped off to China in the Marines to escape some minor problem. After only a year in Peking he had been sent to the Philippines, arriving just in time to welcome the Japanese Army. He was captured in Bataan and came to NiiGata with the American contingent.

I went along with him and two guards to town, to purchase the instruments and look for some medicines, and from then on we became very close friends.

The long summer evenings gave all of us a little leisure time, a luxury we had not enjoyed since coming to Japan. George organized a small combo with his trumpet, a guitar and banjo, and gave small informal concerts on the playground. I think that this did more for camp morale than could be ever imagined. The sound of “Star Dust” bursting out of George’s trumpet created a warm civilized aura that masked the cold reality around us.

Unfortunately there were no books available, not officially that is, another reflection of our captors’ paranoia. However, I had smuggled “A Pocket Book of Verse” with me from Hong Kong, and it was my greatest treasure. When I worked in the coal yard I tried to memorize a small passage every night to bring with me the next day. It helped keep me sane in a mad world. By the time the war ended it was a badly battered volume as I shared it with Bill Stewart and George Francis. I had intended to take it home with me but lost it with most of my other “treasures” when I jumped ship in Hawaii. Fortunately it was still in print then and I now have another copy in my library.

Instead of reading there was now a good deal of conversation. Even rumours made their appearance again, a sure sign that our spirits had revived.

We had a few old China hands in the camp and I particularly enjoyed listening to their tales of a world that now has vanished. To a man they were confident that China would never go communist, as the Chinese were far too much family orientated and individualistic. They must have been surprised at the apparent complete obeyance to Mao for so many years. Perhaps time may prove them right, as fifty years in China is but a few minutes in the day of their history.

One of the more interesting characters in the camp was Arthur Rance. He was perfectly fluent in Japanese; in fact he always amazed the Japanese themselves, as few gaijin (foreigners) attain complete fluency. He had been a sergeant in the Hong Kong Volunteers and had been sent on our draft. He was a brilliant man with a keen sense of wit. He helped me learn some Japanese and more importantly gave me a bit of insight into some of their puzzling national characteristics, particularly their hidden caste system, the awesome importance of saving face and their different attitudes to approaches that we might consider devious.

Bill Stewart saw more of him after the war as both were involved in the War Crimes trials. It transpired that Rance’s mother had been a Japanese nurse who had married an Englishman. I guess Arthur never wanted us to know he had Japanese blood in his veins. He died from cirrhosis of the liver in Vancouver shortly before I arrived there, having become an alcoholic. What a pity! He could have become a success in almost any field with his intelligence and charm, to say nothing of his complete fluency in Japanese.

As the reader can imagine, there were very few secrets held back between friends in this setting, where tomorrow was a vast unknown, which makes the following story unique.

I had an uncle on my mother’s side who had been involved in some scandal in the military, but it was more or less of a family secret and I knew very little about it. His name was Chris Duffield and he was a graduate of Sandhurst.

My grandfather had risen from a private soldier to become Colonel of the Royal Ulster Rifles, which was a rare rise in rank in those days. Uncle Chris’ fall from grace was a family tragedy not to be discussed in front of the children.

As Bill Stewart had been raised in Belfast, I asked him if he had ever heard of the case, but he said he had not.

After the war, I learned from another relative that Chris had been a subaltern in Gibraltar and had shot the colonel of the regiment. It was a sensational item in the press of those days. Apparently the murdered man had been making homosexual advances and putting pressure on the younger officers. Because of this Chris was not hanged, but was sentenced to a long prison term. He later went to Kenya and during the war was the Regimental Sergeant Major of the African Rifles, serving in the European theatre.

When I went to visit Bill many years later in Britain, I told him of this and he smiled.

“I did not think I should tell you since you were not aware of all the circumstances. I knew all about the affair as my wife’s father was in charge of the court martial.”

How typically British; I admired him the more for it.

I wish I could have met Chris. He did attend the wedding of my sister Margery, who was a Nursing Sister in the Canadian Army in England at the time. He was by all accounts a great guy. He later became the editor of The Kampala Times in Uganda. During the unsettled days that plagued the country he was attacked by robbers, losing an eye, and he never really recovered from these injuries, dying in his adopted country.

Major Fellows, the American Camp Commandant, was an authority on the American Civil War and loved to talk about it. Some evenings he would give semi-formal lectures on his pet subject and I was most impressed. By the time peace came I knew by heart most of the commanders and all the problems of the significant battles. After the war when I lived for three years in the American South, my American friends never ceased to be amazed that a Canadian could explain to them what really happened at the battle of Vicksburg. We were spared three weeks of work in the worst part of the following winter by a lucky turn of events. Early in December, 1944 a microscope was acquired and Bill Stewart started doing some stool tests. It was hardly surprising to discover that there were many cases of amoebic dysentery.

When the Camp Commandant was told of this he went wild, knocked us all about and blamed it all on the inadequate medical care.

Much to our surprise the next day a Professor and some students from the University of NiiGata Medical School appeared armed with microscopes and stool testing equipment. Work parties were suspended and stool tests were done on everybody. These confirmed the results of Bill Stewart. The Professor suggested a mass quarantine, mass treatment and general improvement of the sanitary facilities. All of these were very welcome, especially the three week suspension of work. That year was one of the worst for snow and wind in NiiGata’s history. We were covered with drifts up to twenty feet high, so this rest came at an opportune time. I doubt that there was much change in the incidence of amoebiasis, but the whole operation no doubt saved many lives because of the rest. The action of the Professor was quite courageous as the authorities were anxious to keep the work parties out and active. It was reassuring to see someone in the medical profession who retained some compassion and had not succumbed to the pressure of the military.

John Stroud, one of my fellow prisoners, tells me that he wanted to ensure the worst possible scenario was presented to the investigating team. He had severe amoebic dysentery that made recognition of the parasites and ova in the stool an easy task. (Microscopic diagnosis can be difficult.) He gave samples of his positive stool to some of the more healthy chaps to pass in as theirs, an unusual gift that may have influenced the ultimate decision to quarantine the camp.

Spring came and once more we envied the geese honking as they flew free and high on their way to Manchuria for the summer. Would we ever be free again? Freedom is such an abused word today. One of the few benefits of having been a prisoner is to know what it really means.

It was another beautiful summer. The work parties went out daily, but there was not much work to be done as few ships were getting through the blockade. Those that did were being sunk by mines dropped in the harbour or more dramatically by American planes, with their rockets zooming into the ships. They flew in unopposed, not even by any anti-aircraft fire. This was a novel experience for us, as our only use of rockets had been as firecrackers as children.

When Germany surrendered I tried to persuade Bill Stewart to demand his release as he had been captured by the Germans. He did not appreciate my sense of humour. We heard of the American victories in the Philippines, Okinawa and Iwo Jima. Some of those in command in Tokyo must have begun to get the jitters as all the tough guards and honchos were slowly replaced. Among those who left was Corporal Takeo Takahashi, the medical orderly who had made life and death so miserable in those early days.

The average Japanese was quite prepared to fight to the death, or at least so it appeared to us. George Francis and I were concerned as to what would happen when the Allies finally invaded Japan proper. No doubt there were many fanatics prepared to toe the official line.

A large pit had been dug outside the camp. We were told it was to be an air raid shelter. We suspected it was designed as a mass grave for the prisoners if the Americans landed. That this was indeed the case has been revealed by the publication of the orders that were issued by Field Marshal Terauchi in the summer of 1945.

“At the moment the enemy lands on Honshu, all prisoners are to be killed.”

George and I saved precious little scraps of food and each had a small haversack ready for such an emergency. The plan was to break out of camp and head into the countryside if everything looked bad. It just might have worked, but happily our plan never had to be put into action.

It was a daily routine for B-29 bombers to fly over NiiGata but we were never subjected to the mass bombing like many of the other cities. Usually they dropped large mines, one of which fell into Shintetsu Camp rather than the harbour.

One plane was shot down and a survivor was brought into camp before being sent to Tokyo. He was isolated in a cage near the guardhouse, a small jail within a jail so to speak. I managed to speak to him and get some of the latest news. It appeared that an invasion was imminent. He couldn’t believe how strange we all looked and the odd clothes we were wearing, as he could see the work parties going out each day. I only hope he was not later beheaded as some pilots were, even as late as one day before the capitulation.

That summer I had a unique experience. One of the guards approached me as I was sitting outside the medical room one evening. I had by now enough Japanese to carry on a small conversation. He gave me a cigarette which was not that unusual and then out of the blue said: “Can I trust you? “I did not know just what to expect, but naturally responded: “Of course.”

He told me that he was a socialist, had been very much against the war, that Japan was on the verge of losing and finally that he was disgusted with the way we were being treated.

I reacted with caution, fearing a trap, but gradually realized he was being quite sincere. We met quite frequently and he brought us in some medicine from the local black market. Bill and the other officers had been paid in yen, but had never been able to spend any, except for the musical instruments. This useless paper suddenly became a useful currency. He later also became a fresh source of news. All this was done at no small risk as the both of us would have been severely punished had our little exercise been discovered. Then his group was suddenly transferred and I never saw him again.

Alter the war I received a card from him saying that he was Mayor of his town and doing very well. Unfortunately I lost the card and was too busy adjusting to a return to school to follow it up. I should do this some time as the card was reproduced in the Quebec Chronicle Telegraph, being sent there by my mother before forwarding it to me.

In July we had another influx of prisoners, 150 civilians who had been captured in Wake Island and interned in Shanghai. In addition there were 200 men, 24 officers and 2 doctors who had been bombed out of their camp in Tokyo. Our camp was now crowded like the old days, but morale was high as fresh news of the destruction of Tokyo and the first suggestion of apparent weakening of the civilian spirit filtered through.

Now Camp 5B became a hodgepodge of prisoners from all the allied forces in the Far East. As well as Canadians and Americans, there was a sprinkling of White Russians from Shanghai, Australians and Englishmen from Singapore who had been bombed out of their camp in Tokyo. Only the Dutch stayed together as a cohesive group. They were the crew of a submarine that had been sunk off Java. They arrived in camp in Hong Kong with scarcely any clothes on their backs, but in three months they had cornered many of the best jobs, controlled the kitchens and were the aristocrats of the camp.

The rest of us lacked such national cohesiveness, and instead most of us had one or perhaps two buddies with whom everything was shared and to whom loyalty was unswerving. Except for this very close relationship life in NiiGata was largely dog eat dog.

As I already mentioned, George Francis and I had become the closest of friends and he introduced me to a more intellectual side of life. Like my friend in Hong Kong, Dai Davis, George was extremely well read and indeed a poet in his own right. So in the absence of books, I received what may be termed an aural or oral education.

Despite the near starvation diet, George maintained an incredible drive and unfailing optimism, even in the face of the most depressing facts, a good counterweight to my negative pessimism. When given weevil-laden rice, others would complain about worms in the food. Not George. Instead he would elaborate on the high protein content. The war for him was always about to end next week.

At that time the Camp Commandant was a Lieutenant Kato. He was tall and big boned for a Japanese and had a vile temper to match his size. He actually improved conditions in the camp, but he would fly into uncontrollable wild rages, followed by apparent periods of remorse. Because of the heavy horn-rimmed glasses he wore he was known by all the prisoners as Four Eyes. He exercised the strictest discipline not only with us but with the guards as well. His vile temper and sadistic bent earned him the rueful respect of both prisoners and guards. Anyone who moved on roll call might be beaten unconscious with the flat of his sword. He beheaded the unfortunate young American Mormon, who suffered hallucinations and left camp to join the “advancing Americans”.

Four Eyes took special pride in six chickens in an enclosure behind his quarters. Almost every morning he would begin the day by going into the chicken house, collecting the eggs and murmuring affectionately to his brood. Perhaps they were the only creatures he had ever loved.

To fully comprehend what follows it is necessary to understand a characteristic common to most prisoners. Most of us had a fixation on what he would do on that distant day when freedom finally came. Perhaps this was a defence mechanism to keep body and soul together, to make meaningful the meaningless.

One friend’s great ambition was to run a house of easy virtue in Montreal and have all the beds fitted with orange silk sheets and black satin pillow cases. The last I heard of him he was a shoe salesman in Chicoutimi. I wonder if he still dreams.

My own ambition was more immediate, much more prosaic and perhaps just as unattainable. I wanted one of the Camp Commandant’s chickens.... to eat. One day I made the mistake of mentioning this to George.

“No problem”, he said, “Like taking candy from a baby.” I did not share his natural optimism but over a period of weeks the project became an obsession. We talked about it and weighed the risk, which was fearsomely real, against the return... our first chicken in four years. I did not have the courage of my lack of conviction and we decided to go for broke.

There were always at least two guards on outside duty. Sometimes they would stand by the gate and make small talk. At other times they would walk around the perimeter of the compound, meeting under the unused watch tower at the corner of the camp opposite the gate. In the tower was a bell, presumably for the guards to ring in case of alarm. We had never heard it ring.

Security was quite light because there was no friendly place to go if one did escape. The chicken house, secure behind Kato’s quarters and beside the guardhouse, gave the chickens the assurance of being better guarded than the prisoners.

It was a warm, sultry and cloudy August night. There had been a noisy party in the Commandant’s quarters so we could count on him and a good part of the guard detachment to be somewhat less than alert. No lights were allowed as B-29 raids had been pounding Japan in the past few weeks. Our plan was to distract the guards’ attention while George weaseled in to steal the chicken.

Waiting until everyone was sleeping soundly, we stole out of the quiet hut. I ducked behind the kitchen, being careful not to arouse the Dutch cook, who was understandably on the watch for unusual noises. This brought me to within 30 feet of the guard tower. I reached into my pocket for a sling shot and some small smooth pebbles. From my position I could see that one guard was at the gate and the other was walking down beside the opposite fence towards the tower. I aimed for the bell. My first shot was a way off. The second a little closer. The guard was getting closer to the corner and I was getting shakier. My third try was a complete flop. I was left with one stone.

Bong! ! ! ! ! ! It sounded like Notre Dame. Both guards broke into a run towards the tower. I ducked into the latrine which was hygienically situated right beside the kitchen, and then ran back to the chicken house just in time to see George emerging with a chicken struggling under his arm. The die was cast.

We were both breathing heavily as we sneaked into a room used as a first-aid dispensary. It was crude, certainly, but it did contain an electric sterilizer. Silence was vital as the room was inconveniently located next to the Commandant’s quarters.

While we were fiddling with the sterilizer, the chicken whose neck George thought he had broken, squawked back to furious life, clucking desperately around the floor of the pitch black room. We both flailed out to grab it, afraid that all the commotion would waken “His Nibs”. After what seemed an eternity, I luckily fell on the wretched fowl. This time there would be no resurrection. We plucked and cleaned it, carefully putting all the feathers and innards in my hat, an odd receptacle to be sure, but the camp afforded no such luxury as a bag or cloth or a piece of newspaper.

George came up with an ingenious suggestion. “We’ll spread some feathers behind the guardhouse, and then Four Eyes will think the guards have done it.”

This made a great deal of sense, because the ordinary one star private was scarcely fed any better than we were. Since George had ventured into the lions’ cage, it was my turn to take a risk. So I slithered behind the guardhouse, managing not to attract the attention of the guards, who I could hear still talking about the mysterious ringing of the tower bell.

Hugging the ground, I dug a shallow pit with my hands in the soft earth under the guardhouse window. After dumping the contents of the hat into the hole, I covered the debris with earth, carefully leaving a few feathers showing above the surface, as evidence of the hasty burial. All went without a hitch and I crawled quickly back to the dispensary door. When I returned the chicken was boiling merrily away.

George was hovering over it with the air of a three star Michelin chef.

“Pity we haven’t any chili.” he murmured, “One hour should do it.”

Time limped by unbelievably slowly. We dared not lift the lid of the sterilizer lest the aroma lure a passing guard to investigate.

George finally nodded judiciously and we attacked our prize. Nothing has ever tasted as good as that hen. We ate the whole bird, sucking the bones dry. It was ecstasy.

Dawn was breaking as we belched our satisfaction. We cleaned up the last traces of our mess and started towards the barracks, filled with chicken and pride. Just outside the door, George stopped and looked at me.

“Where is your hat? “, he asked. I don’t remember my answer but in those days it would not have been fit to print. I had left the hat underneath the guardhouse window. It had my number, 124 stenciled on it, an invitation to disaster.

The first gray streaks of dawn were filtering through the clouds. I had to get that hat back, or I would be missing more than a hat. Clearly this was no time to be chicken!

We looked around the corner of the dispensary and my heart fell when I saw both guards chatting by the gate in full view of the burial site.

George whispered: “Hold on for two minutes, I’ll move their butts.”

He broke off in a jog and shortly after I heard him whistling in the square. The guards stopped their gossiping and one of them waved him to return to the barracks. George didn’t move, so the other yelled at him:

“Kora! “Still no action.

They started to move threatenly toward him so he nipped quickly into the barracks. This was my cue. I threw caution to the winds and rushed in to retrieve my hat, now in plain view. I scurried back unnoticed to the barracks, cautiously avoiding the guards who were returning slowly to the gate. Nothing stirred as I wearily made my way to the bunkhouse and pretended to sleep until reveille. My heart was pounding but my stomach was comfortably full.

Lieutenant Kato did not notice his loss for the next two days. Nor did anyone else. George and I suffered in silence, wondering if we had committed the perfect crime. We could not afford the luxury of letting anyone in on our secret.

On the third day all hell broke loose. The Commandant went to collect his eggs and finally noticed that one hen was missing. He jumped up and down, foaming with rage. Then he lined up all the guards and worked them over one by one, slapping them around as they vainly tried to stand at attention.

I don’t think he ever gave a thought to the possibility that a prisoner might have been the culprit. This attitude was confirmed a few minutes later when the corporal discovered the feathers behind the guardhouse.

Four Eyes shouted in triumphant rage and lined up the bewildered guards for a second round. He beat them mercilessly, hitting them over the head with the long wooden stick used by the Japanese for two-handed sword practice. I presume he hoped for a confession. None was offered.

Morale in The Imperial Japanese Army fell to a new low. For the prisoners it was not only an interesting reversal of roles, but the best entertainment in years. Nevertheless, it was apparent that we could look forward to a very bleak winter as food was becoming increasingly scarce and even coal was in short supply.

I have a few scraps of a diary left, beginning about this time, the earlier ones having been left on the ship in Hawaii. Following are some unedited excerpts, which perhaps in their naive and corny style reveal what it was like to be a prisoner at that time.

July 7th, 1945

"Today is gloomy. A cold wind blows dark clouds about the sky, hiding the light and heat of the sun behind them. I too am gloomy. I can think of nothing but the futility of this narrow, cramped existence. I wonder if it is worth fighting. Is the cause a hopeless one? Is life outside just another prison, where your dearest desires, thoughts, ambitions are crushed by reality?

Is there such a thing as happiness? Or is it just another of many illusions? I tell myself I have been very happy in the past, but was I really? Perhaps it was some mere dabbling into something new, just novelty, nothing concrete.

I think that outside these prison walls I shall find it, but am not all that sure.... let alone lacking faith that I shall ever be free... a discouraging dismal but candid thought.

Somehow or other some mysterious power urges me onward, telling me that there is just one more hill to climb to reach the peak. I fear that I am losing my grip as each successive hill comes into view..., yet I know I will never give up. What drives me on I do not know.

Yet again not all days are gloomy. There are as many sunny, bright days as there are rainy gloomy ones. That is something I do know. It makes me smile.”

July 15th, 1945

“A most unfortunate catastrophe struck the camp last Friday the 13th. Some of the men working at the Marutsu Docks were unloading Glycol. It had a sweet taste and they mistook it for something good to drink. They came into camp intoxicated or so we thought. However, in the middle of the night they became violently ill and passed into a stupor, breathing with difficulty. It was only then that anyone realized the seriousness of it all.

Ten of the most serious cases were carried into the hospital and we all worked desperately to revive them, passing stomach tubes and doing whatever else possible with our limited supplies.

Despite our efforts four died, four young lads all in the prime of their youth. Bobby Macleod, a jolly lad who was very popular in the camp. Mac Hawes, the group leader, Jimmy Gard and Roy Kirk who had both recovered from severe amoebic dysentery. Bobby and Mac were very close acquaintances of mine who used to sometimes bring me some of the food they pilfered at the docks.

It seems hard to believe they are dead. Yet again, is death such an important thing? I think I have seen too many die to really fear it. In fact it is the one concrete thing we can be sure of. One merely fears the unknown. Yet I now know death; what I do not know is life and sometimes I find myself very much afraid indeed.”

July 28th, 1945

"Tomorrow I shall be twenty-two. It seems hard for me to realize but nevertheless it stares me in the face. This will be my fourth birthday in prison camp, and like each one before it my most fervent hope is that I should be free for the next one. Never before have I been so confident that this is to be the last. Of course there still are some lurking doubts.

It is so difficult for anyone who has been a prisoner this long to imagine being free once more. I honestly cannot imagine myself ever eating what I desire, drinking with jovial companions, reading, ever enjoying life again.

Four years, perhaps four of my best years have passed away in prison camps. I have changed so much that I can scarcely recognize myself. I have no idea of what I desire to do, let alone can do, to make a living. All I live for is to be free. More and more as the end draws nearer I am able to understand that I may be in for a big letdown. Yet it doesn’t faze me. Just set me free! Surely on my twenty-third birthday I shall have something more to look forward to than a bowl of rice and a pipe of Japanese Kezami.” (a hairlike type of Japanese tobacco).

Early in August on several successive nights all prisoners were made to stand outside the barracks, on each occasion for about two hours. George and I had our haversacks and plans ready, but we never did find out just what prompted these exercises until after the war ended.

On August 15th we noticed an unusual buzz of activity around the guardhouse. Then the entire detachment was lined up in single file. Something strange was up... but what?

The Commandant, after a few minutes delay, emerged carrying a small table radio, which was then hooked up in front of the gate. Then he took his place in front of the guards, and shouted a command. They all bowed reverently at the radio. A quietly monotonous voice from the device droned on as they all remained in a deep bow. Then the entire squad came to attention as the voice ceased and martial music came on. We all watched, fascinated as they made one more bow and then trooped despondently into the guardhouse.

My Japanese was inadequate to begin to understand what had been said, but Arthur Rance who was perfectly fluent in Japanese gave us the glorious news. Of course it was the Emperor speaking and it is worth noting that he began his speech with what has been called one of history’s most massive understatements:

“The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.” He then had gone on to admit that Japan was surrendering and that the citizenry must “endure the unendurable”.

“THE WAR WAS OVER! ! ! !“

It was a strange sensation. I couldn’t believe it. People were hugging each other. Suddenly the prisoners had become people. The cooks doubled the rations for the evening meal and many people were sick. There was no evening curfew as small groups gathered in animated discussion outside. The guards stayed in the guardhouse.

The next morning we all assembled for roll call as usual, the custom being that when roll was called we all numbered off in Japanese. Then Major Fellows would salute Sergeant Ito, the 2/ic, who would strut out wearing his sword to accept the result of the roll call.

This time Major Fellows waited for him to appear; then we very loudly numbered off in English. Major Fellows deliberately ignored the Japanese Sergeant (who was a real bastard and later hanged), and dismissed the parade. It was our last roll call and what a sweet one it was. There was a great cheer as Sergeant Ito turned slowly, obviously confused, and as the guards looked on, stumbled over his sword entering the guard house.

The next day some American fighter planes swooped over the camp, did a few rolls, and dropped some magazines and cigarettes. There was a terrific scramble for these. Someone knew we were here!

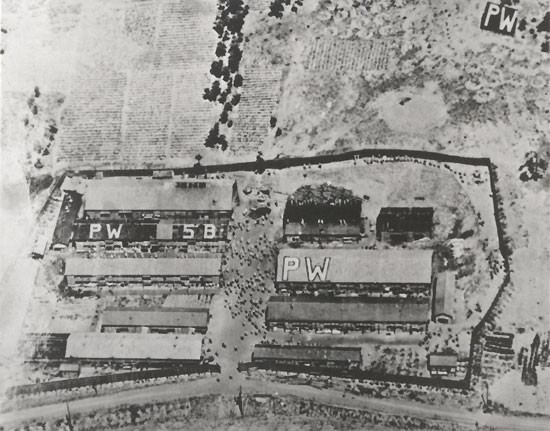

Camp B-5 NiiGata 1945 taken by an American plane dropping supplies. Note the large pit in the upper right hand corner.

We pasted big P.O.W. signs on the roofs. I have no idea where all the materials came from, but I presume Major Fellows got them from the Japanese. It was more fascinating to see several Union Jacks and the Stars and Stripes flying from windows. The proud owners had kept them hidden all these years just for this day.

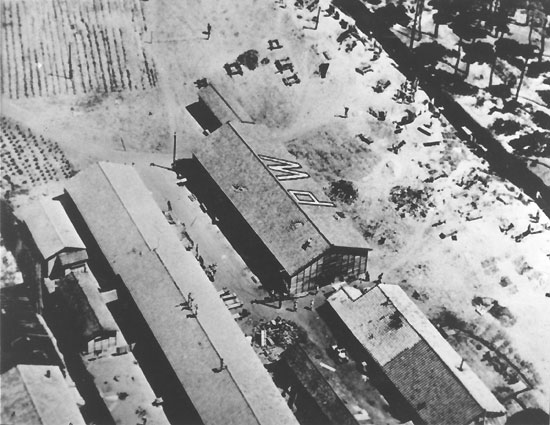

Several days later. Note the holes in the roof from boxes whose parachutes failed to open and how few people are now in the camp.

George Francis and I and three American Marines slipped out of the camp and went into town. It was easy to do, as we simply knocked out some boards of the fence, rather than go through the gate. We walked into the city getting some rather odd stares from the local populace. To our great surprise we ran into an American Navy pilot on the bridge going into the city.

He had just landed his plane at NiiGata Airport... I imagine much against orders as it must have been only about August 19th or 20th at the most. He had commandeered a truck and come into town looking for the P.O.W.s, having flown over the camp and our workplaces during the hostilities.

It was a wonderful feeling that overtook us all. He spoke with a broad Southern accent. We couldn’t believe our eyes and he couldn’t believe what we looked like. He must have been the first free American to land in Japan at the war’s end and must have caught hell when he arrived back on the carrier. He certainly wasn’t mentioned in dispatches! He hailed a passing truck, but it did not stop. He then took out his revolver and the next truck stopped right in front of us.

We brought him back to camp which caused a great furore and was the signal for everyone to go out on the town.

That night the same five of us went down to the city and into a local bar. We were quite rich since we now had cartons of cigarettes. There was an acute shortage of tobacco in NiiGata as in the rest of Japan, so that the weed was more in demand than any currency.

I remember drinking a few cups of saki and then everything went blank. It was the first and only time I have ever passed out from drinking alcohol. I aroused a few hours later in a strange tatami-floored room, with several Japanese ladies hovering over me. The others had left, not too concerned about me. I had a dreadful headache and the setting seemed somewhat eerie.

However, the ladies soon put me at ease, bringing me some rice-cakes and tea. The excitement and saki had overwhelmed me and I must have looked dreadful. All ended well as they brought me a futon and I settled down comfortably for the night, further confirming my positive prejudices about Japanese women.

Shortly after this, huge American planes flew over and dropped supplies.., food, clothing and medicine. There were hundreds of little fires in the camp as small groups cooked this strange food. There were few who were not sick that night.

Bill Stewart and I sat surrounded by the medicine that would have been so useful that first year. We wondered what Penicillin was as there were no instructions with it. We all looked so strange in clean American Uniforms. I even wore a tie, something I rarely do today.

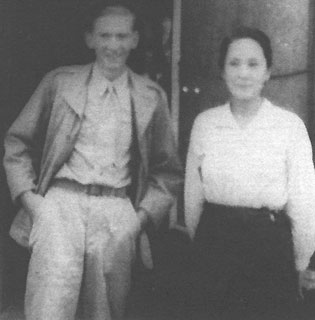

George took a picture of me in my new clothes beside the lady of the Music Shop. She had been very kind to him in the several visits he made there, giving him little rice-cakes and other small goodies, when the guard was not watching. I have the picture in front of me and have difficulty recognizing the scrawny creature in the ill-fitting clothes, but do remember the lady. We brought her a big box of goodies, repaying an old debt.

The planes kept coming. Some dropped their loads too close to the ground for the parachutes to open and the boxes crashed through the roofs of the barracks. One came right into the dispensary missing George and me by inches. Some missed the camp completely and two civilians were killed. However we would brook no criticism of the pilots.

Shortly after this, some heavy torpedo bombers appeared over the camp, did a few rolls and dropped more food, cigarettes and magazines. In them I found a note that almost brought tears to my eyes.... and still does."

U.S.S. LEXINGTON

TO FORMER AMERICAN PRISONERS OF WAR:

Hearty success in your approaching liberation which will occur tomorrow in conjunction with the landing of airborne troops of the U.S. ARMY near Tokyo. The Marines and Navy will follow shortly so it looks like there’ll be a hot time on the Ginza any minute now. We hope that the contents of this package will aid in making your last few hours behind walls more pleasant.

Some of us here on the ships and in the Islands like to tell ourselves it has been a tough war and we really had it rugged. But we know that you are the ones who have made the sacrifices and we humbly doff our white caps in admiration and respect.

Accept our deep gratitude for the deeds you have performed and the suffering you have endured in hastening this day of final and complete victory.

This package was dropped from a U.S. Heavy torpedo bomber flying from the deck of THE LEXINGTON (the Blue Ghost). These goods were gathered by the photographers of The Lex and they are also doing the dropping.

May our aim be straight and true. We wish you all the best of luck and a speedy return to Stateside, the land of milk and honey. When you reach the end of your journey and the excitement has passed away, sufficiently for you to find the time, we would be very glad to have a letter from any and all of you. We expect to be around these waters for a while and would like to know how things are with you.

Signed,

J.R.J. SMITH, BURLINGTON, INDIANA<

R.I. BAILEY, 406 OILDALE DRIVE, BAKERSFIELD, CALIFORNIA

C.V. TURNER, 867 BRATTON ST., JACKSON, MISS.

D.F. TENNEY, 4534 PENN AVE., PITTSBURG, PA.

The last notation in my NiiGata diary reads as follows:

August 23rd, 1945

“I have literally grown up in a prison camp. Most of all my experience has been on the more unpleasant side of life... starvation, sickness, cruelty, robbery, torture, depravity.., all overshadowed by death. Death, that if it was not ever present, always loomed on the horizon.

The experience has given me some insight into my fellow men and more importantly into myself, stripped of the veneer of civilization. I don’t think it has made me cynical, but it has turned me into a supreme skeptic.... skeptical of anything and everything. Despite this, I still think there may be a general grain of goodness in the wood.

Each of us is so absorbed in himself that his vision of others is blurred. It is a bad mistake to think that Joe Blow thinks himself the insignificant individual that he might appear to you. That is one thing I have learned and through it have been able to better accept my own insignificance in the universe.

I must make every effort to remove from myself the intense hatred and disrespect I have toward my ex-captors. I must banish from memory the pangs of hunger, the cruelty, the sadism, the torture, the smell of death of the last few years.

Life lies ahead. I will grasp it and wring it dry to the last drop. There are two promises I make to myself on closing this notebook:

One is that every December 25th, I must pause amid the festivities of Xmas and ask myself: “Am I still a prisoner?

The second is that when I am overwhelmed on being introduced to some sophisticated, immaculately dressed person, to quickly picture him pushing a coal car on the trestle in Rinko, so I can see him in a clearer light. How would he look picking up old apple cores and cigarette butts before the other guy gets it?"

We all had a great time waiting for transportation to Tokyo. The Japanese kids in no time learned to beg for chewing gum and candy. We looked up the good honchos and loaded them with food, cigarettes and clothes. There was nothing to be seen of the mean ones like Sato, who very sensibly kept out of sight.

Even the very sick seemed to recover. It was incredible what a few days of good food and happy times would do for those who had been close to death. Only a handful had to be carried out on stretchers.

A fleet of lorries took us to the railway station. This time our reception on the streets was quite different. People smiled and bowed. No one spat at us. No Japanese flags were in sight.

In Tokyo Station we were greeted by nurses and female soldiers. This last was a surprise as there had been none when we left Canada. The Americans were so kind and generous, so organized, anticipating every thing. To this day I cannot tolerate some of the uncalled for criticism so often launched at our American neighbours. We are lucky to have such a great and beneficent people to share our continent. Not that I agree too often with their foreign policy.

From what little we could see, Tokyo was mass of rubble with the odd concrete building standing like a silo on a bare prairie, or a huge, unemptied dirty ashtray. Yet the railway station was untouched. I presume the Allies planned to use the railways once they had invaded the country.

We were run through a gauntlet of bath machines, delousing centres, medical exams and stool tests and sorted out according to nationality, rank and health status. I hated to see my old sweater from Bowen Road days and the hat which had been with me since that fateful Christmas at Stanley Fort in Hong Kong, brutally thrown away, but did not dare protest. Some men were flown to Manila, but our group was ferried out to the giant armada anchored in the bay, an unforgettable sight.

We embarked on the U.S.S. OZARK, and were most impressed at all the room and facilities. In truth, there was a good deal less than we had on the AWATEA which we boarded in Vancouver, but we really were not those same people any more.

That evening, the anchor was raised and we left Japan. I stood on the rail watching the land fade from view.

“I shall never return”, I muttered to myself, sharing the views of all my comrades.

I was wrong, though it took over forty years for me to navigate my way through that ultimatum.