The Japanese Attack

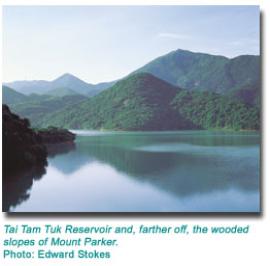

On the night of December 7, we were positioned at a place called Obelisk Hill, so named because of a tall obelisk on the side of the hill, facing Tai Tam Reservoir. On December 8th, the same morning they attacked Pearl Harbour, the Japanese planes came over Kai Tak Airport knocking out the meager air defence of the Colony. They also bombed Sham Shui Po Barracks, and many other installations in Kowloon and on the Island of Hong Kong. A few bombs landed near our shelters on Obelisk Hill, but with no damage to anything except a few shrubs.

From December 8, until a landing effected by the Japanese Forces at Lye Mun on the night of December17-18, we at "D" Coy Headquarters remained in position on Obelisk Hill. "D" Coy Headquarters was composed of Major Maurice Parker, Captain Charlie Price, Sgt. Major Frank Ebden, CQMS Tommy Smith, Cpl. L.T.S. Bill Doull, Rfm. Jim Darrah, L/Cpl. Graydon Heath, Rfm. Bob Boudreau, Byrron Willett, and myself.

From December 8, until things warmed up, not much happened. Except for dodging the odd Jap bomb, things were pretty quiet on Obelisk Hill. One night Rfm. Noseworthy, a Newfoundlander we had recruited when we were posted there, and I were out on guard duty just up wind from the shelter. We got to talking about our fellow defenders and I asked him what he thought about our English friends. Noseworthy said, in perfect Newfoundlandese, "Dem Goddamn Limey's. Dey pack dere blind aunt and give dem bad money." I fell on the ground laughing. Poor Noseworthy didn't make it. He was killed in action.

The Japanese Make a Landing on the Island

On the night of December 17/18, the Japs finally made a landing on the Island in spite of the best efforts of "C" Coy, Royal Rifles of Canada, under the command of Major Wells Bishop. Much can be told about the gallantry of our lads in the opening hours of the war. Their bravery was outstanding.

Day Two of the Fighting on the Island

The next morning we left the shelters at Obelisk Hill and moved across Tye Tam Reservoir to Mount Butler. Here I must digress and describe the system of water collection in Hong Kong. The terrain of the Island, being so hilly, and so densely populated, provides no possibility of obtaining water except for collecting what falls as rain. To make the most advantage of the steep hills in every part of the Island, deep concrete drains have been built around the hills. These drains, known as catchments, are some four feet wide and about the same depth. They wind around the hills and lead to the reservoirs where the water is collected and treated before being fed into the water mains of the city. The reason for my digression will soon become clear.

Here my thoughts are a bit hazy, but I recollect that I was with Colonel, then Major Price, who was second in command of the Regiment, on a road near the reservoir. We were under fire from the invading Japanese, and I thought my chances , at that point, would be better on the far side of the road. I dashed across followed by a spray of machine gun fire reminiscent of Rambo movies out of Hollywood. Major Price yelled, "Get down you damned fool. That bullet had your name on it." In my youthful bravado, and not realizing the danger I was in said, this is no lie, although I am not proud of my response, "Yeah, but it didn't have E/29986 on it." My service number. Now ... I think that was stupid.

Special mention must be made of Gander, a Newfoundland dog, a huge, gentle,

lovable animal, a favourite of all the men. We had adopted Gander as a mascot

when we were stationed at Gander.

The story has oft been told. Gander's bravery

was duly recognized with the awarding of the Dicken Medal in the autumn of 2000

in Ottawa by Sir Roland Guy of the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals in

England. A moving ceremony took place at the residence of the British High

Command, Sir Andrew Burns. As a footnote, Fred Kelly, now gone, who had been in

charge of Gander in happier times, received the medal on behalf of the Royal

Rifles of Canada and handed it over to the Canadian Military Museum, where it is

now on display.

The story has oft been told. Gander's bravery

was duly recognized with the awarding of the Dicken Medal in the autumn of 2000

in Ottawa by Sir Roland Guy of the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals in

England. A moving ceremony took place at the residence of the British High

Command, Sir Andrew Burns. As a footnote, Fred Kelly, now gone, who had been in

charge of Gander in happier times, received the medal on behalf of the Royal

Rifles of Canada and handed it over to the Canadian Military Museum, where it is

now on display.

Photo: Gander, then called "Pal", with some of the kids of the family who had him before we adopted him. Picture was taken at Gander Newfoundland.

Rescue From The Water Catchment

All water for human consumption in Hong Kong is collected from the rain in giant concrete ditches called "water catchments", described above.

During a heavy rain these ditches fill to overflowing.

During a heavy rain these ditches fill to overflowing.

On December 20, we were ordered to evacuate our pill boxes on Obelisk Hill and move across Tai Tam to positions on the other side of the reservoir. The Japs had moved rapidly from their landing at Lye Mun and had occupied a superior position at Tai Tam Reservoir. We were ordered to the top of the hill, Mont Butler, overlooking the reservoir from the north, and by walking up the catchment soon reached our objective.

There were Japanese in plain view in the plain below us, with mules, field pieces, and an armoured car moving across the bridge over the reservoir. We opened fire as soon as we saw them and sent mules and men cart wheeling, and the armoured car came to a halt half way across the reservoir.

The Japs had a six inch mortars, and they were deadly accurate. They had us in view and launched mortar bombs at point blank range. Bullets whistled by my head, clipping the grass beside me. It was Winston Churchill who said, "Nothing is so exhilarating as to be shot at and missed." He was right.

The fire was so intense that we were ordered to withdraw, but not before we had suffered some casualties with several of our company killed, and several others wounded. Among them was Jim Durrah, our Company Quartermaster Storeman. He received a bullet in the leg, just below the knee, which shattered the bone.

Here we were, a mile or so up the mountain. Night was approaching and it started to rain heavily. We had no medical supplies except "first field dressings" that everyone carried. Someone bound up Jim's leg and we carried him on a stretcher made up of two rifles and a blanket that somehow had found it's way to the top of the hill. The Japs now had the high ground and were sniping at us in the water catchment. We had to keep our heads down below the edge of the ditch. We were in trouble.

(Photos above and below courtesy of Jeff Yam )

A Narrow Escape

The rain was falling hard and before long the water began to rise in the

catchment. Although we were taking turns carrying Jim, who kept imploring us to

leave him behind, the struggle was enormous.

The rain was falling hard and before long the water began to rise in the

catchment. Although we were taking turns carrying Jim, who kept imploring us to

leave him behind, the struggle was enormous.

Soon the ditch was full to the brim, and the water flowed quickly. We had to carry our burden high so that he wouldn't drown and at the same time we had to keep our heads down or risk getting shot.

Jim was a big man, about six feet tall and weighing about two hundred pounds. Our discomfort must have been insignificant compared to his, but he complained little. The makeshift stretcher on which we carried him was about half his length. His head and shoulders hung over one end, and his wounded leg hung over the other.

We finally reached the bottom of the hill in the pitch dark, and someone found an empty warehouse. On a hard cement floor, in soaking wet clothes, tired and hungry, in close proximity to the enemy, I had the best and deepest sleep of my life. Jim is still with us, thank God, although, recently, he had to have the wounded leg amputated.

He worked for the New Brunswick Forest Service until his retirement just a few

short years ago. He lives with his wife, Mary, in Centerville, New Brunswick.

He worked for the New Brunswick Forest Service until his retirement just a few

short years ago. He lives with his wife, Mary, in Centerville, New Brunswick.

A post-script to this tale might be worth a mention. On the way down the hill, to ease my load while helping to carry Jim, I shucked off my small pack. In the pack, among other things, I had were some cigarettes and a copy of The New Testament that my Mother had given me when I was home on embarkation leave.

On waking the next morning in the warehouse someone, I forget who, handed me my pack. In the pack was my New Testament, which I still have, dog-eared from the soaking it got in the water-catchment, and my frequent reference to it in the prison camp later.

What happened the next day has fled my memory, but on the second day after the action near Tai Tam I was with Lieutenant Ian Brakey in an exchange of fire with some Japanese troops at a place called Palm Villa. They withdrew and left a machine gun on the edge of the water-catchment. We spent the night waiting for them to come and reclaim it so we could get a shot at them,but they didn't come.

Repulse Bay Hotel ... Lots of Rooms, But Not A Place You'd Want to Stay

One afternoon, probably about December 22, Major Parker sent me to look for Lieutenant Simons. I started off on foot up the road toward Repulse Bay. I was soon overtaken by Cpl. Roblee driving a three-ton civilian truck that he had commandeered somewhere. He had several bottles of brandy with him and a pair of pistols strapped to his waist like General Patton.

We stopped at the Repulse Bay Hotel, and after ascertaining that Lieutenant

Simons was not there, we started back. The road then, as now, is quite narrow

and winding, with stone walls along the way ... where the road overhangs the

cliff. When rounding a bend a little too quickly, no doubt with the senses being

a little dulled by the brandy, we struck the stone wall and wrecked the truck.

We stopped at the Repulse Bay Hotel, and after ascertaining that Lieutenant

Simons was not there, we started back. The road then, as now, is quite narrow

and winding, with stone walls along the way ... where the road overhangs the

cliff. When rounding a bend a little too quickly, no doubt with the senses being

a little dulled by the brandy, we struck the stone wall and wrecked the truck.

I was sitting in the passenger's seat on the left side, and I was thrown up against the windshield. My head contacted the bar dividing the windshield and it was only my steel helmet that saved me from a bad head wound. As it was I got cut on my right temple and have the scar to this day.

Roblee helped me back to the Hotel, where a pretty nurse patched me up, and insisted I stay in the safety of the hotel. I resisted, and started back, walking, to report to Major Parker that I had been unable to find Lieutenant Simons. How fortunate I was. The next day the Japanese attacked the hotel where "A" Company of the Royal Rifles of Canada were positioned. "A" Company had a hard time defending the hotel and took many casualties. The civilians billeted there wanted the troops to surrender to appease the Japanese. An adverse report on the conduct of the defenders reached the ears of General Maltby, Commander in Chief of the Defence Forces in the Colony. It is assumed that the complaints of the civilians influenced the assessment by Maltby of the Canadian troops efforts in the defence of Hong Kong. Oscar Robertson, a nearby neighbour, and boyhood friend before the war, was killed at Repulse Bay.

Sleeping Too Near the Enemy

Somewhere along the road I met Bob Boudreau who was also in "D" Company and had been a runner. Night was descending so we decided that we had better find some place to wait. There was a pill box nearby, just below the road. Bob wanted to go in, but something told me that it would be dangerous to do, so we lay down on the flat roof of the pill box. In the morning we heard unfamiliar voices, and sure enough, there was a detachment of Japs milling around on the ground below us. We didn't breath. After they moved off, probably to join forces with the attackers at Repulse Bay Hotel, we got down. We were hungry and thirsty, not having had anything to eat or drink since God knows when. In the pill box we found a can of condensed milk. We punched a couple of holes in it with a bayonet and drank it. Pretty strong stuff on an empty stomach. Now, every time I see a can of condensed milk I think of Bob Boudreau and the close call we had that night on top of that pill box. In our position we had no way of reporting the incident, or any way of informing Army Intelligence, of the presence of the enemy.

There's 15 Japs in Stanley Village

By December 24, we had been pushed back to Stanley Fort, a British installation on the top of a high promontory. accessible from the rest of the island through a narrow isthmus, and Stanley Village, located on a broader part of the isthmus. We were billeted on the bottom floor of a four or five story building, and if I recall correctly, even though mortar shells kept landing on the top of the building, we had some rest on Christmas Eve.

Christmas morning Major Parker came in and told us we were assigned to clear out a small party of Japs in Stanley Village, located on the isthmus below the fort. We understood that there were on 15 Japs there, so the task would be quite easy. How naive of us to swallow that story. The whole Japanese invading force was massed behind whatever detachment was holed up in the bungalows at the graveyard, and could have, and did, reinforce them as soon as the action started.

Photo courtesy of

Tony Banham

Photo courtesy of

Tony Banham

The object of our attack was Bungalow C where only 15 Japanese soldiers were supposed to be holed up. It sounded like an easy enough chore, but it turned deadly in very short order, and a lot of men died.

We girded our loins and began the trek to the village through the main gate, and across the open space to the right, to the edge of the cliff, and down the cliff to Stanley Village. All the way across that open space we were followed by Japanese artillery fire. They must have had an observation post overlooking our line of progress, but we couldn't spot it.

One of Mother's Gospel songs kept going through my mind, "Will the circle be unbroken?" I couldn't help thinking of my family back home, but no doubt concerned for my own safety. I was scared.

The only casualty on that trip across open space was Lorne, Molly, McIntyre, a Rifleman in 18 Platoon. He got a shard of shrapnel in the buttock, and when he sat down, he sat in a mess where someone had previously had a bowel movement. Lorne's reaction, with blood pouring from his wound was, "Some dirty bastard shit in the grass."

Seventeen Platoon spearheaded the attack on the graveyard where the Japanese had positioned themselves. They soon found out that the numbers of invading Japanese had swelled to several hundreds, and the resistance was insurmountable. Many of my close friends died that day, among them, Bert Irvine, Jack Lyons.

One chap pulled the pin out of a grenade and, in his excitement, shoved it into his pocket. The blast blew the front of his pants off. Seconds later he was mowed down by machine gun fire.

A Jap grenade landed at Gordon Murray's feet. He kicked it and it exploded, but fortunately, the worst effect was that he got both his legs peppered with small fragments. Bad enough, but it could have been worse. He was lucky.

According to Lance Ross, Big Ed Bujold stood there pulling the pins out of grenades and hurling them like baseballs through the windows of the bungalow at the graveyard.

By this time Major Parker, Byron Willett, his batman, and I had reached shelter behind the wall of Stanley Prison, the walls of which were some 15 feet high. Japanese shells were coming over and landing inside the walls of the prison. On the ground, just outside the wall, and directly in line with the shelling, was a stack of boxes about 8 feet high. Major Parker said, "Byron, what is marked on those boxes?" Byron said, "T.N.T." We left there in a hurry.

Ursel Kaine's ankle was broken by a Jap bullet, but he managed to hobble to safety and was rescued. Morris Delaney was shot in the head, just over the left ear, a sort of glancing blow. He staggered past me and I spoke to him. He said he was going to the dressing station. I was surprised to learn later that he died soon after. It was said that he was a victim of what in now called "friendly fire". Who needs enemies?

Sgt. Major Frank Edben stopped a bullet right on the point of his chin, which broke his jaw and ripped out eight teeth. Frank survived and returned to Canada where he lived until the early 90's. Frank had been a bugler in WW1. After returning to Canada in 1945, he continued to play the bugle in spite of the disfigurement of his lower jaw. He performed at all our cenotaph ceremonies.

Forced Withdrawal

Because our losses were so heavy, and the continuing pressure of the

overwhelming hordes of Japanese troops, we were forced, once again, to withdraw.

Major Parker turned and counted the ragged remnants of "D" Company, the Royal

Rifles of Canada. Of the 120 men who had gone into action in Stanley Village

that Christmas Day, 1941, only 45 went back up the hill. Major Parker's eyes

streamed with tears as he counted us.

Because our losses were so heavy, and the continuing pressure of the

overwhelming hordes of Japanese troops, we were forced, once again, to withdraw.

Major Parker turned and counted the ragged remnants of "D" Company, the Royal

Rifles of Canada. Of the 120 men who had gone into action in Stanley Village

that Christmas Day, 1941, only 45 went back up the hill. Major Parker's eyes

streamed with tears as he counted us.

Photo: Major Maurice A. Parker

I remember the feeling of utter despair as we faced certain death, because we were being forced into a dead end zone at the fort. The possibility of swimming to Llama Island some distance away entered my head. It's just as well I didn't attempt it. I would never had made the island, and even if I had what would have happened to me then? Llama Island, as far as I knew, had nothing but a few Chinese inhabitants and, for their own safety, they would probably have had to be unfriendly, if not hostile. I figured it really wasn't the place for a bedraggled refugee from the Battle of Hong Kong.

In addition such an action would have been regarded by the Canadian Army as desertion in the face of enemy fire. In the worst case scenario I could have been put up against a wall, blindfolded, and shot, or I might still be in prison.

Another possibility entered my head. Suppose the British Navy could affect an

evacuation like the one that had happened at Dunkirk? But, by that time the

Japanese Navy had sunk the two British Battleships, The Repulse, and the Prince

of Wales, as they made their way north in the China Sea.

Photos: H.M.S. Prince of Wales H.M.S Repulse

The Bitter Taste of Defeat

When we got to the top of the hill and began out retreat over the shell-holed terrain we had traversed that morning night was falling, and the shelling continued. I found myself beside Lance Ross. When the shelling increased he told me to lie on my side and place my rifle along the side of my body as it could offer some protection from the exploding bombs.

"A" Company, of the Royal Rifles of Canada, had been sent out to relieve us but, before they could reach us the order to surrender had been issued and, the battle was over.

I was told that as "A" Company moved out of the fort they were caught in a

barrage of shell fire causing a number of casualties. It was there that Frank

Cormier was killed. I was told that there wasn't a mark on him. Apparently a

shell had landed close to him and he had been killed by the concussion.

Shortly after we got back to the Fort we were informed that Governour Sir Mark

Young had ordered the surrender of the Colony. The reason we were given was that

because the invaders had cut off the water supply and electric service the

civilian population had demanded capitulation. Who knew what our future held.

Prisoners of War

At that time we also got the rumour that the Germans had been turned back in their invasion of Russia. With our efforts in the defence of Hong Kong at an end it seemed there was a little bit of hope that we would live to fight again another day. I remember the mixed feelings I had on receiving the news of the surrender. My life had been spared, a cause for rejoicing. But, as a soldier, I was a defeated man, A prisoner of war. Not a glorious way to end a military career. I still think of it.

The Questions Remain

There are many reasons to ask why so many bungles were made in the defence of Hong Kong. One may ask why a small force of 120 men were sent out to chase out, what was reported to be, "15 Japs in the village"? If we had intelligence of the numbers of Japanese occupying the village why were more troops not sent to carry out the mission?

According to an informed report, over 2000 men were marched put of Stanley

Village several days later under Japanese guards. Where were they on Christmas

Day when "D" Company, the Royal Rifles of Canada, were being cut to pieces in

the cemetery in Stanley Village?

It is not hard to deduce where they were. I distinctly remember that a vigourous

game of soccer was in progress on the Square in Fort Stanley that fateful

Christmas morning, 1941.

Total Surrender

The next morning we stacked our rifles, the last act before total surrender, and the equivalent of presenting the sword to the victor. That was the last I saw of my Enfield, number 1-59544. I had carried it from Valcartier in July, 1940. We had always been admonished to respect the rifle, "the best friend a soldier ever had". I had taken to heart the advice that had been given to me. The rifle had become a part of me. To this day the feel of a Lee Enfield against my shoulder is like an extension of my body, almost like a third arm.

Visiting the Past

In 1994 Arnold Ross, Roger Cyr, and I were part of a pilgrimage that visited the battle sites and cemeteries in Hong Kong.

We are pictured here on a slope overlooking Stanley Military Cemetery, at a spot where Roger told is that it is the place where he last saw Bill Fallow. Bill Fallow was killed at St. Stephen's Hospital on Christmas Day, during the Japanese rampage in the Hospital.

Left to right, Phil Doddridge, Arnold Ross, Roger Cyr.