Memories of Bill Nugent

Ted Terry

I am Edward (Ted) Terry jr. Son of

Capt. Edward L. Terry Sr., paymaster of the Winnipeg Grenadiers

during the battle of Hong Kong in 1941. In 1942 my dad died while

a pow in H.K. When I was young my mother told me stories regarding

my dad and his best friend

Lt. William (Bill) Nugent Platoon Commander of ‘C’ Company W.G. 's,

who was awarded the Military Cross for bravery in the battle of H.K.

Bill returned from H.K. to Canada after almost 4 years of captivity. I

don’t remember ever meeting Bill after the war. But I frequently saw his

sister Lillian. When I was young I was a puppeteer and Lillian

created the costumes for my marionettes. Over the years I had

every intention of getting in touch with Bill, but I never did.

Recently my memory was stirred when I read in our HKVCA newsletter the

name of Bill’s wife and that Shelagh Purcell had been unable to reach

her. I thought, that’s not odd as Bill’s wife would be around 100

years old now. I got the phone number from Sheila and I called.

The phone was answered by Bill’s daughter Mary Nugent who informed me

that her mother had passed away a few years ago. Mary and I had a

long and wonderful conversation. She told me that her dad Bill had

passed away at only 53 years of age. She also told me that he was

a wonderful father to her and her older sister but, like so many other

veterans, he never spoke of his experiences during the war. That

is likely why I never heard from him. I had to tell Mary a

terrific story about her dad. In prison camp, my dad knew he was

not doing well and likely to die. My dad gave Bill his wedding

ring to keep safe and to try to return it to my mother after the war.

My mother told me that Bill wore the gold ring on a toe inside his shoe

for three years to keep it from being taken from him by the Japanese

captors. After the war he brought it to my mother in Ottawa. She

was shocked and extremely grateful to Bill. Mary had never heard the

story and I was really pleased to tell her and add it to her good

memories of her dad.

Memories of Alfred Babin

Mike Babin

My Dad, Alfred Babin (RRC), stayed in the Army after the war, and

finally retired from active duty in 1971 as a Warrant Officer. He was a

quiet man, and not given to talking much about himself. So when I was

young - although I knew that he had been a soldier in the war - I didn’t

know much more than that, and certainly nothing about the horrors of

battle and the brutality of the POW camps. It wasn’t until I was in my

30s, when he and my Mom, Christina, had started attending HKVCA meetings

and conventions, that I began to ask him about his wartime experience.

He was always willing to speak to me about it, never over-dramatizing

but always giving lots of detail. He had brought home only a couple of

items … a cloth patch with his POW number and a handmade tobacco

pipe … and was pleased to show them and talk about them.

Mom and Dad had met before the war, and Dad had promised Mom that he

would return to marry her. He often said that it was thinking of Mom

that sustained him throughout the ordeal of his internment.

Our family was lucky: Dad did not have serious health issues

(although he was not in any way a complainer, so any problems he did

have he kept to himself); he was not a drinker; and we had what I

consider to be a “normal”, happy home life. Although Dad did not finish

elementary school, after the war he and Mom worked hard to earn their

high school diplomas at night school. Shortly before his passing in

2014, I learned that Dad had applied to the University of Western

Ontario many years before and had been accepted, but decided not to

attend.

Every photo I have of Dad shows him standing erect and looking

dignified and proper, sometimes with a gentle smile. He was proud, in

his quiet way, of his wartime service and of his long career in the

Canadian military. And I am proud of him.

Memories - The Women of War

Carol Hadley

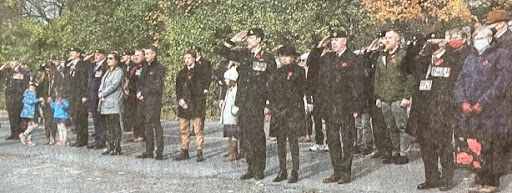

Today as I sit and watch the Remembrance Day service in Ottawa, it is

the first time that I can remember not attending a Service in person.

I think of my family members that served in WWII. I also think of

the women that were left behind to continue to look after the family.

As I reflect on my mother’s life, I admire her strength and

determination. She never took a leadership role that I remember

but quietly went about getting things done. She met my father at a

St. Patrick’s day dance that had many military attendees. They had

a couple of dates until he was sent to Jamaica in 1939 for garrison duty

relieving British troops to return to the war in Europe. They

continued to write and get to know one another. Through this

communication they began to care about one another, so when he returned

in the fall they were married October 18, 1941. A few days later

my father and the other Winnipeg Grenadiers boarded a train to head West

to British Columbia to be shipped to Hong Kong.

My mother continued to live at home to help support her family as her

brother and brothers-in-law were also serving their country. She

worked in Eaton’s department store from leaving school, however the

manufacturing companies needed to replace the men that left to serve so

she became a riveter for Trans Canada, who made planes to be shipped to

the war effort in Britain.

My father continued to write to her with letters of hope and funny

stories that occurred on their journey. The soldiers landed in

Hong Kong on November 16, 1941 and began more training as several of the

men were recruited as they travelled across Canada. There were

stories of how life was good, as their Canadian salary when converted

into Hong Kong dollars gave them many benefits, like rickshaw travel,

busboys to do their laundry, etc. This was good news to the family

back home to know they were safe so far from home.

As we know now this didn’t last long as the Japanese attacked Hong

Kong on December 8, 1941, and therefore communication became

non-existent. News back home was scarce but serious, as they

learned of the Japanese attack and the subsequent fall causing the

colony to become prisoners of war.

For almost 4 years, communication for my mother was checking the

newspaper daily looking for names of those who were killed, missing or

POWs. This stressful time was compounded by the rations of food, money,

etc.

My father was among some of the last soldiers to return home in

October of 1945, after a debriefing in San Francisco and more hospital

time in Vancouver. Because of his war injuries and diseases that

he suffered from, my father spent many years in and out of Deer Lodge

Veterans hospital. The decision was made for my father to leave

the military due to his health. He found work in a mine in

Northern Ontario in 1947, so my mother and I went too.

This was an extremely hard life for my mother as there was no running

water and accommodation was scarce. We lived on an island.

Water was obtained by going down to the water's edge and hauling pail

loads up to heat for cooking, washing or laundry. There was little

transportation on the island, so a lot of walking.

We were there for almost 3 ½ years then came back to Winnipeg where

my brother was born. My father continued visits to Deer

Lodge, where my mother packed up 2 small children to journey by

streetcar to visit him on the weekends. My father continued to

have nightmares, which was very stressful for my mother and at some

point he was given electric shock treatment to alleviate the terrors.

His treatments at Deer Lodge became less frequent and he had a good

life.

My mother’s strength and fortitude to keep the family sustained on

limited funds and supporting my father and 2 small children was a

tremendous feat. This does not diminish the strength and fortitude

of my father as he endured the pain of memories, injuries, disease and

supported his family. My brother and I are fortunate to have such

strong parents who encouraged us to follow our wishes and dreams and

gave us the life skills to be successful. We love them forever.

Remembering my Grandfather- George Thomas Palmer

Michael Palmer, Grandson

My grandfather, George Thomas Palmer, was born on March 6, 1909 in

Newcastle, New Brunswick. He was only four when his father disappeared,

so he and his mother moved to PEI where she raised George into a fine

young man. By early 1940, though, George was looking for an adventure

abroad. With WWII breaking out, he decided to join the fight by

volunteering for active service. Before long, he was with the Royal

Rifles and heading overseas to an unknown destination, soon revealed to

be Hong Kong. He was part of 'C' Force – a Canadian contingent of 1,974

men who were defending the British colony if the Japanese invaded.

Weeks later in 1941, on the same day of the Pearl Harbour attack, the

Japanese advanced toward Hong Kong, which initiated the desperate

defence by the Allied defenders who were only 14,000 strong with

virtually no navy, air force, heavy artillery or reinforcements to

assist them. Facing them were approximately 60,000 battle-hardened,

mechanized, fanatical, tenacious Japanese troops fresh from battles in

China. Little did George or the rest of his comrades know that this

battle for survival would continue for 45 long months. At least, for

those that survived.

George fought the good fight in the hills of Hong Kong for 3 weeks –

taking up perimeters, rescuing comrades, getting shot in the leg and

being hospitalized, and then surrendering to Japanese forces. Once the

battle ended on Christmas Day 1941, George would enter a new phase – to

survive as a prisoner-of-war under the brutally harsh conditions of the

Japanese. He started off at Sham Shui Po POW camp in Hong Kong where he

was involved in an escape attempt with two others. Unfortunately, the

breakout didn’t transpire due to illnesses. By 1943 he was transferred

by ship to Japan where he ended up at Omine Camp to work in a forced

labour camp, toiling in the mines during 12-hour shifts. There were

beatings, severe illnesses, degrading behaviours, starvations, threats

of execution… just horrible conditions. And this went on from 1941 until

late 1945 when, finally, the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. A few weeks later, Japan surrendered.

My grandfather was often asked how he could’ve survived such insanity

all those years. “Hope” was his constant reply. He had much hope that he

would survive the worst the Japanese threw at him. But he almost didn’t

make it. By the time the Japanese surrendered, he was down to 99 lbs (he

weighed about 170-180 lbs when he enlisted in 1940). He and the rest of

the men wouldn’t have lasted another winter in the Omine Camp. I heard

from a few of his comrades that he also had a great attitude within the

camps – always trying to cheer up the men and in one case, stealing an

orange from a nearby orchard for a friend who was deathly sick from Beri

Beri. Any bit of food could help immensely with the assortment of

sicknesses those men endured.

With the Americans finding the camp in late 1945, the men marched out

the front doors and never looked back. Over future weeks, they ate until

their weight returned to normal and then they began their journey home

aboard an assortment of ships. Upon arrival in Vancouver, he travelled

by train across Canada, until he landed back on the good ol’ red soil of

Prince Edward Island and into the arms of his lovely wife, Jeanette. He

put the war behind him and focused on family, farming and the community.

It was time to shake off the war demons and get on with living a

meaningful life. With one child already (from before the war), George

and Jeanette would have eight more. All would grow into wonderful people

with families of their own, products of George and Jeanette’s strong

family values and beliefs.

In 1991, after living into his 80s, George passed away peacefully,

surrounded by family and much love. A life well lived.

(the complete story of George Palmer can be found in his book

biography at

www.michaelandrewpalmer.com)

“My Father”

Norma Fuchs

My father, John Leo Doiron, Royal Rifle, F-40908 was in the Battle of

Hong Kong in December of 1941. He was born into a large farming family

in Hope River, PEI. He had been working on his family farm and for

other farmers in the area until he joined the Royal Rifles in 1940. He

spent some time in Quebec and Newfoundland before he was shipped over to

Hong Kong with almost 2000 young soldiers. They had no idea where they

were going and what was in store for them in the next months and years.

He had met my mother, Alice, not long before he joined up and they

were not married before he went to Hong Kong. She waited for him,

receiving only a couple of short letters the whole time he was in the

camps. When he got back home in November of 1945, they picked up where

they left off and were married in March of 1946. They went on to have

five children in the next seven years and life went on.

Growing up I do not have many memories of Dad talking about the

camps. I do remember that Christmas was an emotional and sad time for

him. I know he tried to make it fun for us; however, the memories

haunted him around the Christmas season.

He worked hard his whole life. I think that was his escape. In their

later years he and mom went to some of the Hong Kong Reunions and

connected with some of the people he knew in the camps. I am not sure

that he really enjoyed that, it seemed to spark the memories again. He

passed away in 2003 shortly before his 85th birthday. I am not sure that

he ever was free of those horrible memories.

A Tribute to her Mom

Marie Gutenberg of Thorsby, AB

Marie sent a letter in response to HKVCA’s request to share stories

about our veterans. Her dad was a Hong Kong veteran, Sidney Blow, a

Winnipeg Grenadier. Marie’s mom, Alice Elizabeth Blow, met Sydney in

1952, when she worked as a nurses’ aide in the Fort Qu’Appelle

Sanitorium. Sidney was receiving treatments for Tuberculosis after he

returned from World War II. They married shortly after, had six

children, and continued their lives mostly on a farm. Her mom was very

talented and resourceful. Marie explained that her mom never cooked rice

for her dad, but he sure loved Chinese food at the restaurant. Our

thanks to Marie for her great letter. (Kathie Carlson)

A Brief History of Club 13 – Friendship & Loyalty

Researched by Megan

In 1932, a young Tillie Balliet moved to Swift Current, Saskatchewan.

At that time, Swift Current was in the midst of the Great Depression.

Yes, the entire world suffered but the prairies seemed to suffer more.

Their economy, built primarily around farming, had turned to dust – much

like the fields that surrounded them. In 1934, despite the challenging

and depressed prairie environment, Tillie, ever the social organizer,

decided to ask a new friend if she wanted to start a club. It sounded

like, with some convincing on Tillie’s part, her friend eventually

surrendered saying “I’ll join the club but I’ll warn you – all I do is

darn socks.” And thus, the Sewing Club – later to be called Club 13 –

was born.

Depending on where you come from or what you believe in, the number

13 can either be lucky or unlucky. For the ladies, though, Club 13 just

sounded more interesting than Sewing Club and so, they adopted the

famously conflicted number as part of their identity. Club 13 was

probably a more appropriate name because, it seems, there was only one

member who sewed. None were “domestic giants”, to quote my Aunt Kathie.

If a member left the group or, in later years, when a member passed

away, she would be replaced so that there were always 13 ladies. This

continued until their 50th anniversary in 1984.

My grandmother, Gladys Corrigan, was not an original member of the

Club but joined soon after it started. She was a member when she married

Leonard Corrigan, she was a member when, in 1941, he joined the South

Saskatchewan Regiment and later volunteered to transfer to the Winnipeg

Grenadiers, and she was a member while he was imprisoned for four years

in Hong Kong. She wasn’t the only one whose husband served in the war,

but she did win the prize every time they played the “Whose husband is

farthest away?” game. These women buoyed each other, and their

friendship deepened as they persisted while the men were overseas.

Club 13 met every Thursday night for 50 years. Imagine the life these

women shared together with all of its triumphs and heartbreaks –

especially during the war. Their bond was profound. Between gales of

laughter and moments of silliness, these friends provided extraordinary

support for each other during the heaviest of times. The “meetings”

would have been an oasis amid their uncertainties, fears, and worries.

How fortunate that Tillie decided to start a club in 1934; she would

never have known how important it would be in the years to come. Her

eyes glistened when she recalled those treasured friends and the time

they spent together. She remembered, with great fondness, all of that

“silly fun” they got up to. “I can honestly say that we had just

wonderful times.”

Mike

Babin

Mike

Babin  Phil Doddridge

Phil Doddridge Jim Trick

Jim Trick Gary Geddes

Gary Geddes Pat

Turcotte

Pat

Turcotte

Gerry Tuppert

Gerry Tuppert

Carol Hadley

Carol Hadley

Sandy Strom, (Daughter of Augustin

Cyr, RRC and niece of Clement, Leo and Wilmer Cyr, RRC).

Sandy Strom, (Daughter of Augustin

Cyr, RRC and niece of Clement, Leo and Wilmer Cyr, RRC).

Shelagh Purcell, Eastern Ontario Rep

Shelagh Purcell, Eastern Ontario Rep

Lucette

Mailloux

Lucette

Mailloux

Gary Geddes

Gary Geddes